9 Cooking Trends From The 1950s That Still Don't Make Sense

Food culture just doesn't do rigid lines. What's in vogue today can turn completely ridiculous overnight; so fast you start to wonder how it ever became trendy in the first place. Why, just a couple of months ago, edible glitter was the thing, and now ... well, it's probably a good thing nobody rushed to open an edible glitter kiosk, the only customers they'd be seeing now would be a single, lonely tumbleweed.

And if you're looking for food trends that have retreated so far into the rearview mirror they've turned modern-day punchlines, look no further than the 1950s. Picture this: the post–World War II fog is lifting, Dwight D. Eisenhower is in the White House, the baby boom is in full swing, and kitchens all over the country — previously left desolate by war rations — are getting a new lease on life. Prosperity and abundance are knocking at the door, and cooks everywhere are eager to seize the moment.

A lot is being done in that pursuit. Almost too much. From the spectacular — vegetables and meats suspended in shimmering gelatin — to the questionable — mayonnaise on everything — to the mundane — the processed food craze — the clamor for novelty is everywhere. Ready to be time-warped straight into the thick of it? Here's a roundup of 1950s food trends that made sense once, briefly, and then very much didn't.

Putting everything in gelatin

A 1950s food revival is in the horizon, and strap in, because it's bringing one very bizarre vintage dessert back into rotation: Jell-O. Now, Jell-O desserts haven't exactly vanished — they're still a popular once-in-a-while treat at potlucks and holiday meals. But back in the '50s, gelatin salads (or desserts) were the height of modernity and sophistication, the dessert of choice if you wanted a standout table spread. Entire meals were centered around them, molds of varying shapes were built for them, and corporate America made a killing dishing out recipes promising picturesque outcomes to home cooks.

The range of ingredients was pretty much infinite. It wasn't frowned upon, for instance, to suspend meat chunks, seafood included, alongside an assortment of vegetables and fruit in one mold. And while that mishmash of add-ins made for a pretty ... unusual flavor combo, the idea behind it wasn't to enjoy the meal, rather to wow dinner guests with spectacle.

Obviously, the today's world isn't lacking for visually-stunning desserts, which is why you might not fully understand why these were so popular back then. But the craze around Jell-O makes a lot of sense in context. Refrigerators had just been flattened into the mainstream and home cooks were almost desperate to exploit their full potential.

A dessert that relied completely on refrigeration was just the thing to show off refrigerator presence and prowess. There's also the fact that aspic, once deemed a luxury food, had now become easy to pull off with powdered gelatin. Combine that with the craving for modernity and the widespread desire to put WWII drudgery in the rearview, and you might just begin to understand the 1950s craze for dishes that dazzles the eye. Even if it might be completely unappealing in flavor.

Mayo in everything

Mayo is a top-tier condiment, no doubt. It might take a while for it to run out — you might have no idea of all the ways you can cook with it — but you'd have no hesitation to restock once it does. You might even have a knack for homemade mayo.

But mayo doesn't play well with everything — something you might know all too well if you've ever tried it in, say, a fruit tart. Don't bring that kind of attitude to a 1950s kitchen, though. Back then, mayo was invited everywhere. Entire dishes were built around it, like layered salads, where it was showcased alongside an amalgamation of other ingredients.

Juxtaposed against translucent gelatin, opaque mayonnaise made for quite the visual spectacle, which is why there were plenty of mayo-centered Jell-O recipes in circulation. Take the cranberry soufflé salad, for instance — a curious blend of lemon gelatin, lemon juice, canned fruit, and mayonnaise. Not born out of a fever dream, but promoted as premium fare, it was even featured in a Hellmann's campaign toward the turn of the decade. And if you found the idea of mixing mayonnaise into your Jell-O mold a little on the nose, you could always use it as a garnish, which is just as great an idea as it sounds.

Why the seemingly boundless obsession with mayo, you ask? Though its use exploded in the '50s, mayonnaise was already a pantry staple in many American households as early as the 1910s. Aggressive marketing from brands like Hellmann's supercharged its appeal, and paired with an era hungry for novelty and creativity in the kitchen, it morphed into a bona fide cultural obsession.

Overcooking for food safety

Almost nothing ruins a meal quite like overcooking. It turns chicken rubbery, blackens slow-cooker brisket, and renders boiled cabbage mushy and pungent. It's a tough outcome to sidestep, one that takes practice, and a willingness to deploy every salvage trick in the book once things go too far. But time-travel back to the 1950s and you wouldn't really need to rescue your overcooked beef with barbecue sauce or go through the hassle of steaming life back into an overdone burger. Absolutely nobody would bat an eye if you set the table with food that had stayed on the stove all afternoon.

While you might recoil at limp vegetables or dry, almost chalky meat, folks in the 1950s may have actually preferred it that way. This was an era deeply obsessed with convenience — and if there's one thing convenience foods excel at, it's being thoroughly, unwaveringly overdone. Peas that taste like they've been boiling on the surface of the sun for days, brown, limp asparagus, and tuna cooked so aggressively it needs a very generous slathering of mayo to approach palatability. As processed foods became a nationwide obsession, their flavor and texture quietly set the standard for what food was supposed to taste like. Home cooks, perhaps in an effort to replicate that familiar profile across the board, ended up overcooking just about everything.

In the 1950s, production and processing standards for meats like pork and seafood weren't yet on par with what they are today, which meant contracting animal parasites like Trichinella from undercooked meat was a genuine concern for home cooks. Mid-century public health messaging leaned hard on sanitation and cooking food until well-done to sidestep the risk.

Use of many specialized now-obscure tools

Everybody likes an easy cooking experience, and boy, have we found a way to get at it. Every kitchen has a broad range of appliances, all designed to make the cooking experience as hassle-free as possible. But however abundant the gadgets in your kitchen, they absolutely pale in comparison to those at the disposal of an average 1950s cook. This was the era of the sunbeam mixer, the chamber stove, the Westinghouse roaster oven, and many more incredibly specific tools designed to completely automate the cooking experience.

In fact, according to an ad from the time, you were considered to be roughing it if your kitchen only had a roll warmer, an electric pressure cooker, a grill, a coffee maker, a built-in oven, and a kettle. A flourishing 1950s kitchen could contain close to three dozen electric appliances, alongside a wealth of hand crank tools with very specific uses.

Having as many gadgets as you could cram into your kitchen was considered the height of sophistication. And why wouldn't it? Electricity — previously out of reach for ordinary Americans — had made its way into the mainstream. American factories — previously held hostage by war production — had turned their attention to domestic households. Pair that with a widespread obsession with modernity and convenience, and you've got a veritable craze for top-of-the-line kitchen gadgetry. A 1950s article, Frozen Foods 2000 A.D.: A Fantasy of the Future, even raved that kitchens would soon cease to exist, in their place a range of appliances that could gobble up work that would have once required a full team of help to get done.

Emphasis on food aesthetics over practicality

Everyday meals just don't quite match up to the culinary masterpieces you'd encounter at a gourmet restaurant. But it is possible to bring a bit of that haute cuisine spirit into your own kitchen without breaking the bank. Sprinkle smoked salt onto a cheap cut of steak for a hit of depth, sauté frozen vegetables on high for those coveted caramelized edges, or sneak bacon crumbles into boxed mac and cheese; just a few ways you can elevate everyday meals into something that feels gourmet.

But while you might be willing to bend over backwards to make your food taste refined, the 1950s crowd was obsessed with something else entirely: presentation. Previously a luxury concept, gourmet cooking had began to infiltrate American kitchens, and home cooks were desperate to seize the moment. But canned food — a household staple at the time — doesn't exactly scream elegance. That's where the concept of 'glamorizing' came in. Everyday dishes were primped up with simple but flashy additions: a handful of shrimp, a bit of crabmeat, maybe some canned pineapple for good measure.

The idea was dress the dish to the nines, even if it still tasted like leftovers; which, in all likelihood, it was. And while none of this makes much sense to a 21st-century eater, it actually tracks in context. 1950s America was obsessed with aesthetics. Products weren't designed merely for utility; they were meant to dazzle. Bulbous, enamel-coated appliances in pastel hues, aggressively assertive chrome on every handle, knob, and trim ... it was an era of keeping up appearances; dinner not exempt.

Following corporate-designed recipes

There's nothing quite like stumbling onto a recipe that actually delivers. But is there an unspoken metric for what counts as a good recipe? Nobody wants something conjured in a sterile corporate environment and passed around with the sole aim of cashing in. A proper recipe is born out of personal — or even generational — trial and error, then plastered on the internet with a pithy backstory as nature intended.

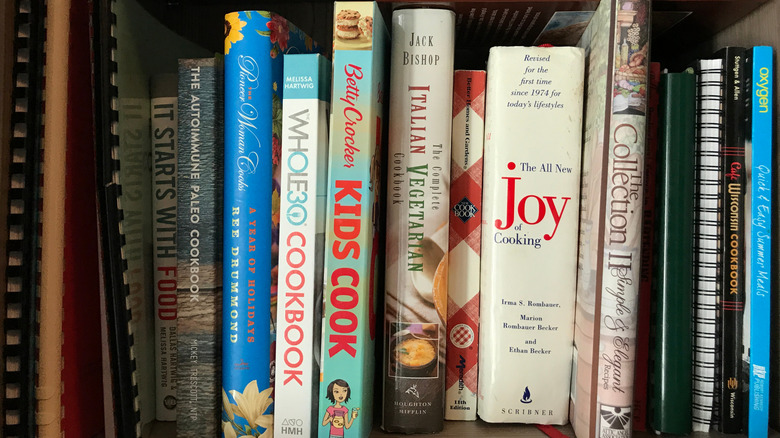

Not in the 1950s. Folks in this era didn't particularly mind corporate-designed recipes, as long as they got the job done. With more women moving into the workforce and household help becoming scarce, home cooks were desperate to simplify the cooking process as much as possible; and corporate America was more than ready to step in and make it all better. There was, of course, Betty Crocker's Picture Cookbook, the brainchild of a General Mills test-kitchen team, whose recipes snowballed so fast that Betty Crocker — a fictional woman — turned into a living, breathing legend.

Of course, General Mills wasn't the only company feeding America cooking instructions. Campbell's printed recipes right on the side of the can. Kraft Foods took out full newspaper spreads littered with recipes built around its French dressing. Corporate America sunk its claws so deep into dinner tables nationwide that some of the most famous — or infamous — dishes of the decade, like the green bean casserole, were actually hatched up in corporate think tanks and dispatched to home kitchens to supercharge sales.

Reliance on canned food

Fresh food is great ... until it starts going brown and limp before you've even gotten around to using it. And while you won't get the crispy texture and complex flavors of truly fresh ingredients, canned food sure is convenient! As long as you steer clear of red flags — off smells, holes, leaking, molding — canned goods can sit on the pantry shelf for years — a little over a year for high-acid items. But while America still loves its canned food, there isn't much of a frenzy about it, at least not compared to the '50s.

Sure, canning had been around as early as the 18th century, but it didn't really start booming until the early 20th century, when canneries across the country were deployed en masse to supply provisions to soldiers at the front. So desperate was early 20th century America for canned goods, it become one of the most heavily rationed commodities all through WWII. But with the dust of war settling in the late 40s, these factories no longer had a ready, booming market for their goods. Something had to give, and that something ended up being ordinary American households.

Food companies were aggressive and somewhat ruthless in marketing their canned wares. Television commercials showed blissful housewives in pristine pastels whipping up one-dish meals from an assortment of canned goods and serving the dazzling outcome to overly-enthusiastic prop families. They sold convenience, efficiency, and most importantly, the relish of leaving the drudgery of making food from scratch in the rear view; ideas home cooks — busied by the demands of post-war home life — were more than willing to gobble up.

TV dinners

Frozen foods might now be big enough to make royalty out of Trader Joe's, but they weren't much of a money-spinner at the start. The whole industry wouldn't have had a prayer were it not for the now-obscure TV dinner. Sure, frozen foods were already a simmering concept as early as the 1920s. But despite being among the least rationed foods during the war effort, there wasn't much excitement around them. All that changed in the early to mid-1950s, when Swanson marched in and marketed them within an inch of their life.

The masterstroke was, curiously, piggybacking on yet another obsession: television sets. TVs were still something of a novelty in the early '50s, but by 1955, TV ownership had ballooned, with nearly a third of American households acquiring a set. Swanson's marketing struck right at the heart of this frenzy. The food arrived in neatly compartmentalized aluminum trays and was packaged in boxes illustrated with a too-perfect replica of the meal, framed by the outline of a vintage television set.

The message couldn't have been clearer if they'd screamed it: the lulling hum of the television is what you need to enjoy this food. Now ingratiated to a populace that was already absolutely besotted with television, TV dinners were well on their way. The rest was sheer serendipity. Refrigerators with separate fridge and freezer compartments had just hit the mainstream, meaning households, supermarkets, and corner grocers alike suddenly had the freezer space to stockpile boxes of TV dinners. There was also the fact that women had entered the workforce in droves post-WWII, and with the demands of the home still heavy on their shoulders, meals that could be prepared in under 30 minutes seemed like the best recourse.

Cream-based sauces

There's a reason a fair number of haute cuisine dishes are anchored on cream sauces. Pasta folded into a velvety cream sauce is absolutely heavenly on a lazy afternoon. But however high you'd rate your devotion to creamy sauces, it's nowhere near the level of fixation reached in the 1950s. Why was that crowd so thoroughly besotted?

Like many 1950s food fads, this one was also — at least partly — brought about by the rapid proliferation of canned foods, particularly condensed cream soups. There was an almost untamable frenzy around cream of mushroom. Marketed as a ready-made sauce base, it showed up everywhere. It was folded into casseroles, slathered onto burger patties, pressed into service as a shortcut gravy, and — perhaps most frequently — deployed as a mercy blanket for dinners that had gone a bit off the rails. Recipes for French mother sauces, loosely "rebuilt" by combining one or two cream-based canned soups, also began popping up, a godsend for women hankering to spruce up mundane dinners into something at least expensive-adjacent.

The era's elaborate entertaining culture fueled the obsession. With most households operating without hired help, hosting was no longer as simple as issuing a barrage of instructions to a round-the-clock team. Outside the very upper crust, most hostesses were cooking themselves; yet still expected to deliver on the unspoken promise of refinement. Coupled with hors d'oeuvres as humble as carrot curls, frankfurters, stuffed cucumbers, or a bowl of gherkins, well-executed cream sauces offered a relatively accessible way to signal polish. Outdoor grilling, too, was sweeping the nation, and cream-based sauces found a ready home in barbecue staples like potato salad or even the occasional tossed salad.