Old-School Delis Aren't What They Used To Be. Here's Why

There's a certain magic to an old-school New York deli — the thinly sliced cured salmon, the towering pastrami sandwiches, the sense of ritual and rites of passage unchanged for generations. But to truly understand these institutions is to know they were born from a strict, delicious logic. In the late 1800s, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe established a dual culinary universe on the Lower East Side. There's the "delicatessen" for meats like pastrami and corned beef, and the "appetizing store" as a sanctuary for buttery lox and briny herring, their existence dictated by kosher law that forbade mixing milk and meat. This was the ecosystem that fed a community.

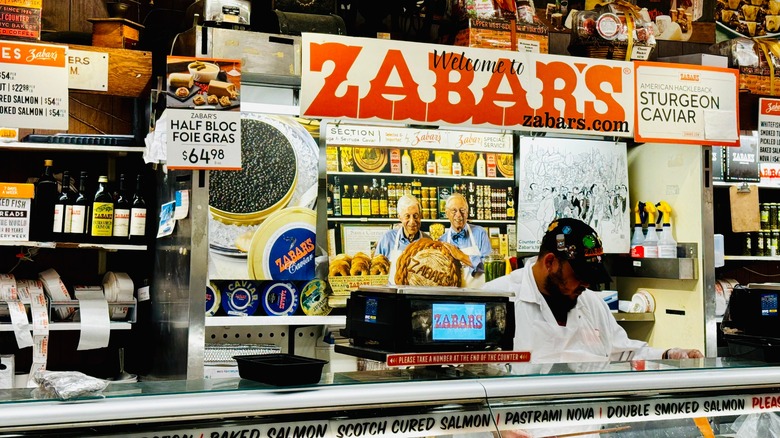

While the golden age of that deli standard may have passed, its spirit endures in the places that have adapted without losing their soul. To understand this delicate balance, we look to a family that has navigated this evolution for nearly a century: the Zabars. Founded by Louis and Lillian in 1934, fiercely built by their sons Saul and Stanley, and now stewarded by the third generation — Annie, Aaron, and David – Zabar's is a direct line to the heritage of deli culture. From day one, the family famously carved its own path as a "kosher-style" store, a flexible identity that allowed it to thrive alongside its community. By looking through their eyes — at the traditions preserved and the ones thoughtfully updated — we see a blueprint for how the classic deli ideal continues to define New York's appetite. We had a chance to speak to David Zabar and Willie Zabar for their thoughts on how and why the deli has changed.

Nova is now the norm

Here's a quick way to date yourself at a New York deli counter: Just order the salmon. "There's a generational divide between fans of traditional lox and Nova Scotia salmon," confirms Willie Zabar. The confusion is understandable, but the distinction is clear. True belly lox is cured for a long time in salt alone, resulting in a powerfully sharp, almost briny flavor that seasoned regulars adore. Nova Scotia salmon, or what the Zabar's call "Novy," is cured for a shorter time with salt and sugar before being cold-smoked, giving it a milder, sweeter profile that has won the mainstream (and this is how long it can last in the fridge).

This is more than a matter of taste; it's a changing of the guard. "Most people these days prefer Novy whether they know to call it that or not," Willie observes. "Lox is a favorite of the much older customers. It's definitely the 'old-school' order." For those seeking that original deli experience, he offers a guide, "Pile a bagel high with lox and red onions if you want to do a little time traveling." You can't go wrong either way.

Brave the wait at the famously busy smoked fish counter, and you'll witness true artists at work. These master slicers, considered the best in the city, handle each order with surgical precision. You can't rush perfection.

Scarcity changed the smoked fish platter

The 75-year partnership between Acme Smoked Fish and Zabar's, as documented on TikTok, has long defined New York's smoked fish counter. But that iconic platter has been quietly rewritten by necessity. "There are items that customers miss because they are no longer available," confirms David Zabar, who was the store's smoked fish buyer throughout the 1980s. He lists the casualties from a bygone menu, "Canadian lake sturgeon, chubs (a golden smoked mini whitefish), wild-caught Atlantic smoked salmon known as Eastern or Gaspé, and some exotic forms of herring."

Where you might have found glistening slabs of these varieties a generation ago, you're now more likely to see sustainable alternatives. This menu change is the direct result of overfishing and environmental shifts in the Great Lakes and Atlantic waters. The evidence is right there in the case: The classic combination has evolved, with some traditional stars replaced by more abundant species like sockeye salmon or Arctic char. The deli platter, that centerpiece of Jewish appetizing, tells a new story now — one where tradition meets the hard facts of modern ecology and proof that even our most cherished food institutions must adapt to survive.

Tongue is a tough sell to swallow

Beef tongue holds a symbolic place in Jewish culinary heritage. Some Sephardic communities, for instance, serve it during the high holidays as a wish to move forward in the year ahead. This reverence carried over to the classic deli, where tongue became a staple sandwich, prized for its rich, tender texture, and always on rye. At Zabar's, this tradition continues among older connoisseurs who are very specific about their slices. "They were always very clear if they wanted it cut from the base or from the tip," recalls Willie Zabar, who worked the counter through college. According to patrons on TikTok, these customers are so devoted they'll travel from other states for what they call "the best in the world."

But for younger generations, this meat is a much tougher sell. Willie (who is also a comedian) perfectly captures the generational shift with a confession, "Personally, I never order the tongue. Maybe I've sliced too many of them, maybe I've dated too many vegetarians, maybe I've spent too much time thinking about the metaphysical implications of a tongue tasting a tongue." The fate of tongue — still beloved but oft misunderstood — shows how deeply cultural shifts are reshaping the classic deli order.

Herring is now a self-service affair

There was a time when ordering herring at an appetizing store was a personalized experience. A counterman would expertly select a whole barreled fillet, slice it to your preference, and pack it fresh. For David Zabar, who began his career in the 1970s selecting fish at Brooklyn smokehouses, this ritual represents a core deli craft. "Though we still pickle our own herring," he notes, "they are now packed in our self-service case, whereas we would have sliced and packed the fillets to order at the counter."

This shift from service counter to self-service case marks a significant, though subtle, change in the deli experience. The personalized interaction, the specific request for a thicker or thinner cut, and the hands-on service have been traded for the efficiency and consistency of pre-packaged containers. But fret not: That in-house pickled herring is masterfully made into old-world recipes. The classic old-fashioned and the cream sauce preparations ("to die for," says one Redditor) remain authentic. While the service at the counter has modernized, the commitment to the product is as old-school as it gets.

Wrapped butter replaced the block

For David Zabar, the soul of the retro deli wasn't just in what you bought, but in how you bought it. It was a multi-sensory experience of craft and connection that modern efficiency has softened. This is particularly true for butter, which serves as a historic partner to smoked fish, traditionally served on rye bread long before the bagel and cream cheese era. "Some of the things I miss are cutting fresh butter to order from a 20-pound block, strings of dried mushrooms hanging behind the appetizing counter, and barrels of self-serve olives," he recalls.

These elements were more than quaint decor; they were theater. The act of slicing a specific portion of butter from a massive slab, the visual spectacle of hanging mushrooms, the briny scent and reach-in thrill of the olive barrels — all created a tangible bond with the customer. As David notes, "COVID-19, convenience, sanitation are all reasons some of these are no longer with us, but they added to the connection."

Their disappearance marks a fundamental shift. The deli has streamlined, trading the messy, personal drama of discovery for the predictable convenience of pre-packaged goods. The flavors may remain, as does superb counter service, but losing the butter block is the kind of small change that inspires nostalgia from deli dyansties.

The big brunch shop is bygone

While the exact origin of New York brunch is nebulous, its Sunday brunch tradition owes a significant nod to the city's Jewish community. Among the deli machers, many frame it as a distinctively Jewish Sunday ritual: a meal laden with bagels, smoked fish and schmears that filled the social and cultural space church occupied for others. This evolved into a weekly habit where grandparents would buy provisions "in quantities to feed an army," according to David Zabar. He has watched this shift firsthand, noting the change in how families gather and shop. Willie Zabar chimes in, pointing to a symbolic end of that era, "The only bygone tradition I'd bring back would be to keep Zabar's open until midnight on Saturdays," when post-theater crowds would stock up for the next morning's feast.

Though the epic Sunday shop may be a faded tradition, one delicious argument remains a weekend unifier: the long-raging debate over what makes a New York bagel superior. That passionate discussion over a chewy boil-and-bake specimen (versus Montreal's wood-fired, honey-sweetened version) still brings people together. Our shopping habits may have changed, but our devotion to the core classics remain as strong as ever.

Curt counter service has softened

Some of the most memorable deli orders aren't about food, but for a style of service born from classic New York intensity — a city where most are overworked, in a hurry, and value blunt expertise over pleasantries. Willie Zabar recalls a waiter who outright refused his friend's order for traditional lox, insisting "you want the Nova" with the confidence of a culinary authority. This brand of in-your-face hospitality has become increasingly rare in the age of online reviews and customer-centric service. "Those gruff waiters and countermen are a dying breed," muses Willie.

That soul is now tempered by the sheer scale of modern success. These days, Zabar's is a 20,000-square-foot behemoth serving around 40,000 customers a week. When you're moving 4,000 pounds of fish in that time, the math is simple: Efficiency must trump the art of the argument. While today's smoother service is easier on the ego, the disappearance of these culinary curmudgeons marks the sunset of an age where your server's opinion was part of the meal. In the end, it seems sheer volume vanquished that vibe.

Some delis have lost their legends

In today's hospitality scene, you rarely find staff who have become institutions themselves. But at Zabar's, the legends are part of the foundation. This living legacy was built by pioneers like Saul, who abandoned his plans to be a doctor to run the shop after his father died in 1950, then spent half a century alongside his brother Stanley expanding it into the culinary empire it is today. Though Saul's recent passing leaves an immeasurable void, the culture he built endures.

That steadfast presence now passes through the steady hands of 95-year-old master slicer Len Berk, who answered a counter service classified ad that led to him selling his CPA practice. "After 40 years in the world of finance," Berk recalls in an article for Forward. "I traded my suit, tie, calculator and computer for whites, a plastic apron, a sleek, slicing knife — and I love it." Hired by Saul himself, Berk represents a direct, human link to the old-world tradition. In fact, Willie Zabar mentions that you can still see him behind the fish counter every Thursday. In an age of faceless corporations, Zabar's good name confirms that the most essential ingredient remains the personal touch of impeccable service.