Experts Reminisce On Beloved Soul Food Dishes We Rarely See Anymore

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Soul food is an essential part of America's culinary origin story, an edible history of Black resilience and creativity that emerged from the South. The cuisine has its direct origins in the agricultural practices and foods of West Africa, which were adapted and transformed by enslaved African Americans using available ingredients. Through remarkable ingenuity, these cooks developed a distinct culinary tradition from limited rations and foraged foods, creating dishes that sustained both body and spirit across generations.

Yet, as this cooking tradition moved from rural landscapes to urban centers and into the modern era, a subtle but significant shift occurred. An entire catalog of beloved, resource-driven dishes began to fall out of common practice, pushed aside by a narrower, more commercially viable version of the soul food we know today. This journey into the soul food canon goes beyond the well-trod path of fried chicken and macaroni and cheese to rediscover the nearly forgotten classics. These are the dishes that tell a deeper story of community, seasonality, and survival.

To guide us through this essential rediscovery, we turn to some definitive voices on the subject: Adrian Miller, aka the Soul Food Scholar, and Nicole Taylor, whose influential "The Up South Cookbook" is now celebrating its 10th anniversary since publication. A James Beard Award-winning author and culinary historian, Miller lends his expert historical perspective on these dishes, while nominee Taylor provides insight into their enduring cultural resonance, together explaining not just how they were made, but why they are cherished.

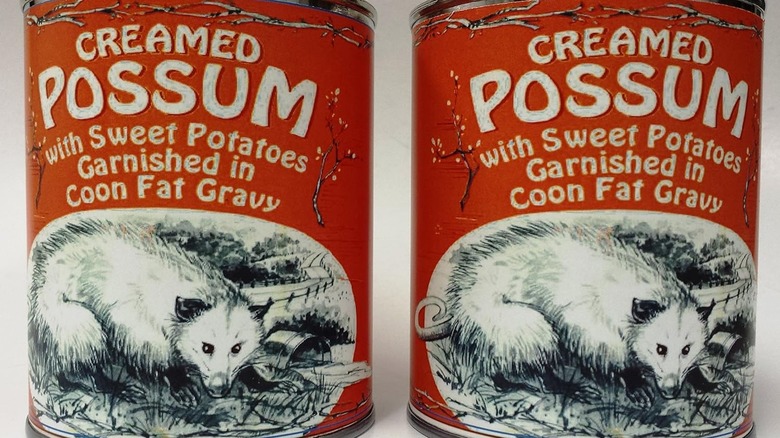

Opossum and sweet potatoes

Imagine a time when the most sought-after holiday centerpiece wasn't a ham, but a roast possum; its rich meat slowly baked with a garrison of sweet potatoes glistening in the pan gravy. A century ago, opossum and sweet potatoes was a delicacy that Black epicures held in high regard. Its story is a direct and flavorful consequence of the Great Migration. As Adrian Miller notes in "Soul Food," "When it came to cooking possum, the standard method was to bake it with sweet potatoes... The sweet potatoes were enriched by cooking in the possum's gravy," resulting in a taste often described as remarkably similar to pork.

This dish's roots run deep, with Native Americans enjoying possum long before European and African arrival, a tradition they shared with colonists. The hunt was part of the ritual: Typically, hunters would chase the animal until it climbed a tree, then shake it from the branches to be captured. Its preparation continued this careful process, sometimes involving fattening the animal on milk and grain before a slow roast. Yet, this culinary chapter has largely closed. "As families moved from rural areas to cities," Miller observes, "their reliance on game like possum and raccoon dropped off considerably." The skills for hunting and preparing it, along with the urban codes that forbade such practices, faded, turning a once-beloved dish into a poignant symbol of a bygone way of life. "Sweet potatoes on the soul food table are not endangered," says Nicole Taylor, "o'possums, for sure."

Squirrel fricassee

Before squirrels were park-bound panhandlers, they were a prized protein, a tradition with deep roots in Native American cuisine that was adopted by European settlers and enslaved African cooks. This cross-cultural exchange was first embodied by a hearty, slow-simmered stew of squirrel and vegetables believed to be a culinary gift from Indigenous communities to early colonists. Then there's the evidence of squirrel bones near slave quarters that tells a story of resourcefulness, where trapping and stewing this clever game was a common practice.

Its fall from grace was a perfect storm of post-war urbanization, the loss of hunting grounds, and a profound cultural makeover. As squirrels became the charming, bushy-tailed heroes of children's books, the very idea of eating them became unthinkable to the modern diner. Yet today, a curious revival is afoot. A new generation of chefs, championing hyper-local and sustainable game, is rediscovering this forgotten delicacy. Driven by this culinary ethos and even conservation efforts to manage invasive grey squirrels, squirrel fricassee is cautiously returning to adventurous menus as a taste of a deeply rooted (and surprisingly elegant) culinary past.

Rabbit okra soup

The tradition of rabbit simmered in a slick, savory soup predates its more famous pairing with dumplings. This hearty dish offers a direct culinary link to West Africa, where the technique of using okra's natural mucilage to thicken pepper pots was born. This is a method preserved and perfected within Gullah Geechee culture along the coastal South, suggests Nicole Taylor, where rabbits were found on the chopping block and okra soup was a mainstay.

It's a profound expression of the African diaspora: foraged rabbit from the American South mingling with this ubiquitous pod, a foundational ingredient and technique carried across the Atlantic. The result is a uniquely textured, gelatinous broth that remains an integral part of the cuisine.

The decline of this dish maps directly onto the journey from rural self-sufficiency to urban life. The need to hunt rabbits waned as communities moved to cities, where ingredients were store-bought and traditions streamlined. While okra's place on the Southern table is secure, the rabbit's journey from foraged game to family pet severed a crucial link. Nevertheless, Taylor thinks this beautiful protein has a place on fine dining menus. "Salt of the earth," she says of the rabbit.

Hog jowl and cowpeas

In the soul food pantry, few pairings were as foundational as hog jowl and cowpeas. This pairing was the epitome of resourcefulness, applying a flavorful cut from the whole hog to transform simple legumes into a deeply satisfying meal. As Nicole Taylor clarifies, while "cowpea" is a term now used to describe a family of Southern beans, its origins are transatlantic. The seeds were brought directly from West Africa, a cherished foodway forcibly transplanted by the slave trade.

Its role evolved from practical to symbolic. A New Year's tradition of eating pork, specifically cuts like the cheek, emerged from the folk belief that a pig, by rooting forward, symbolizes progress into prosperity. The cowpeas cooked with it, their round shape evoking coins, came to symbolize good fortune. This specific practice is a convergence of customs: While West African spirituality included sacred days, the focus on the first calendar day for luck is likely more European.

Urbanization, however, made the hog jowl a near-relic. Pre-packaged ham hocks became more convenient than a whole hog's cheek. These days, unless you see its unsmoked cousin, guanciale, on the menu, fresh pork cheek is more likely the star of the plate and cured ham hocks are what make cowpeas shine. Yet, as Taylor reminds us, the heart of the tradition endures, "When I think of soul food, I'm looking for peas cooked down with smoked meat. The real Southern peas: crowder peas, lady peas, purple hull peas."

Fried American eel

While catfish may claim the undisputed title of the Friday fry, fried American eel was once a seasonal staple for Black communities along the South's rivers. Cooks fried the fatty catch in a cast-iron pan, yielding a crackling, savory crust — a simple act of kitchen genius that traveled well beyond the South. This tradition migrated with Black pioneers who settled in places like Nova Scotia from the mid-18th century onward.

The tradition stayed alive in kitchens, many for whom it was simply a taste of home. Today, this slippery specialty has all but vanished. Its decline is a story of dual pressures: a cultural drift from river-based life and a sobering ecological crisis. The American eel is now endangered, with harvests plummeting from millions of pounds annually to a fraction of that. What was once a common, crispy staple on both sides of the border is becoming a ghost of culinary memory.

True pit barbecue

The soul of American barbecue lives in the earth itself; the hand-dug pits that served as the original smokers. As Adrian Miller outlines in "Black Smoke," a key narrative places the technique's transfer to the mainland with European colonists who observed Caribbean barbacoa in all forms — fish, rabbits, and snakes — later applying the method to more familiar livestock. Enslaved Africans in the South adopted this practice, merging it with their own culinary wisdom to create a bedrock of the soul food tradition. "This was pit barbecue in its purest form," explains Miller. "Not modern convenience, but actually digging a hole in the ground, chopping trees, burning wood to coals, then cooking a whole pig or lamb."

This foundational practice, however, could not make the journey to the city. The Great Migration brought pit-masters to urban centers where health codes, a lack of space, and nuisance laws rendered the tradition impossible. The communal earth oven was ultimately supplanted by commercial smokers — a pragmatic evolution that preserved barbecue, but sacrificed its most profound and ancestral expression.

"You ain't rolling up to no barbecue spot in a big major city — you see smoke, you see wood, but the practice, you have to seek it out," Nicole Taylor adds, highlighting the constraints that made true pit barbecue a rarity. In this vacuum, barbecue culture adapted, with fiercely guarded regional identities becoming tied to signature sauces, distinctive sides, and specific cuts across America. As Taylor succinctly puts it, "There's no space in big cities for a pit."

Cracklin' bread

There's a world of flavor in a humble pan of cracklin' bread, a type of cornbread studded with crispy bits of pork skin salvaged from rendering lard. This skillet-baked delight was the seasonal reward for a community's hard work, transforming the prized byproduct of a hog killing into a shared promise of nourishment through winter.

According to Adrian Miller, you'd be hard-pressed to find that bread on a restaurant menu today. Without families gathering for hog butchering, those fresh cracklings have mostly disappeared from our communal kitchens. What remains is the memory of cooks who knew how to turn every part of the pig into something special, creating a loaf that celebrated both full bellies and good company. "Whoever was cooking would put in a few cracklins... but to see it at a modern soul food spot would be a rarity these days," adds Nicole Taylor. Whether you're a Southerner born and bred, a culinary history buff, or simply inspired to taste this tradition, learn the lexicon of pork fat, then get your oven hot, your cast iron greased, and listen for that glorious sizzle when the batter hits the pan.

Cornbread and buttermilk

A spoon, a glass, and two humble ingredients were all it took. "Cornbread and buttermilk lights me up!" Nicole Taylor reminisces. The simple ritual of crumbling day-old cornbread into a glass of cold, tangy buttermilk created a dish that was both a before-supper snack and an anytime solace. This simple combination was among the South's original comfort food, one that has largely disappeared from modern kitchens, a casualty of changing palates and commercial dairy production.

"We don't really drink buttermilk anymore," Adrian Miller muses. The thick, cultured buttermilk that once gave the dish its distinctive sharpness has been replaced by thinner alternatives that can't replicate the original experience. What remains is a cultural divide: For some, the mere mention of cornbread and buttermilk sparks deep nostalgia. For others, it prompts pure bewilderment. Either way, this unassuming glass tells a story of rural resourcefulness that's faded from tables yet remains alive in spirit.

Southern tea cakes

More than a simple cookie, Southern tea cakes represent a tangible heritage of Black American culture and have a forever home in the soul food kitchen. Born from the ingenuity of enslaved bakers who worked without written recipes or measuring tools, these sincere cakes were perfected through memory, transforming European inspiration into something distinctly soulful. These humble treats became threads in the social fabric, marking rites of passage at events like baby showers and representing "so many positive images of Black life," Nicole Taylor observes.

Once a staple of home kitchens, the fresh out-of-the-oven tea cake is now a rarity, largely replaced by artisanal shops. Yet their significance has deepened, serving both as a symbol of hard-won freedom in Juneteenth celebrations and, for those who still bake them, a heartfelt gesture. Every batch is a direct connection to ancestors who turned simple ingredients into a legacy of love and perseverance.