15 Blueberry Cooking Mistakes We're All Guilty Of

Blueberries by the handful are one of nature's most delicious fruits — especially when snatched straight off the bush on a lazy summer morning. Many people enjoy these jewels daily when they are in season, sprinkling them over morning cereal and late-night chia pudding. The only other berries people like more in the United States are strawberries. But there's more to this bulbous berry than eating it raw; cooking blueberries deepens and concentrates their flavors in dishes both sweet and savory. Heating adds complexity that goes beyond sweetness, especially when the berry is paired thoughtfully with complementary flavors.

Take care, though: Blueberries can quickly turn on you if not properly prepared, leaving you with a sad, weepy mess that's gluey and flavorless. It is possible to avoid oddly colored batters and cook blueberries with confidence, though. If you're new to cooking blueberries (and even if you're a pro in the kitchen), here are 15 mistakes you might be making when cooking blueberries.

Using unripe blueberries

If you're shopping at your local farmer's market, chances are good the blueberry vendors will offer you a sample before you buy their wares. But when a sample's not available, some shoppers simply grab whatever clamshell seems okay. Don't be that shopper. Unripe blueberries are tart and not as sweet, which can affect the flavor of whatever's on the menu.

The trick to choosing the tastiest blueberries in the grocery store starts with evaluating their color. Blueberries should be deeply colored, not light pink or green — anything other than dark blue indicates an unripe berry. Look for blueberries that are plump and firm to the touch (it's okay to open the clamshell to see). Avoid wrinkled or mushy berries, as these characteristics can indicate age or damage during transport. The last thing to keep in mind is size: It truly doesn't matter. Some varieties of blueberry can be as large as a quarter, while others are barely the size of a BB. Stick with color and texture as your main indicators of ripeness, and you'll do just fine.

Not washing and prepping blueberries properly

Blueberries used to be harvested mostly by hand to preserve the integrity of the fruit and to select only the best berries. These days, larger commercial farms use machines to pick the blueberries, often before every bunch is ripe, to speed up the process and save labor costs. While this can bring the price of blueberries down at the market, the end result is a pint or flat of berries that may be bruised and unripe and left with stems, leaves, and even a stray bug or two. Washing and prepping berries properly can prolong their life and improve the quality of your finished product.

There's some controversy about whether or not you should soak your fruit in water, but blueberries benefit from a quick dunk in a bowl with a splash of vinegar right before you are ready to use them. This removes pesticides and dirt. Strain blueberries and use a salad spinner to remove all of the water (or pat dry with paper towels). Go through the berries by hand to remove stems, small twigs, and any leaves or other dirt. This process can be more challenging if you are preparing smaller varieties like wild Maine blueberries, but it's worth it to remove all of the dirt, stems, and errant insects that stowed away with your fruit.

Overcooking blueberries (or cooking with too much heat)

Few people pass up a handful of fresh blueberries tossed into granola, chia pudding, or a late-night bowl of ice cream, but these versatile berries can do so much more with the judicious application of heat. Cooked berries become sweet and flavorful, but overcooking them can result in a culinary disaster. Unless you are creating a silky smooth blueberry sauce (or even one with a few chunky berries), take care not to overcook your fruit.

Overcooking blueberries breaks down the thicker outer skin. While this works well for a puree if you're going for a pie, sauce, or jam, overcooking results in a mushy texture that more closely resembles the inside of the berry. When it comes to overcooking, the biggest culprit is using too much heat. Gently cook blueberries without bringing them to a boil to retain their shape. And remember: If you change your mind and want a more jammy texture, you can always mash them later, but once blueberries are overcooked to mush, that's a bell you cannot unring.

Not adjusting the amount of sugar

A characteristic that separates home cooks from professional chefs is that professional chefs taste their ingredients before they cook them. You can have 1,000 blueberries that are perfectly ripe and deliciously sweet, followed by one mouth-puckering batch that sucks all of the moisture out of your mouth. It's critical to determine what you're working with so you can adjust the amount of sugar or other seasonings you'll need so that the true flavor of the berry shines through, not the cloyingly sweet flavor of sugar. While every berry has an individual level of sweetness, tasting a couple can give you a representative sample of the batch.

If you don't want to sample your blueberries before you use them, there's a simple way to guess at their level of sweetness. Since ripe berries are sweeter than unripe ones, gauging how ripe the berries are can help. To test ripeness, pour your berries into a bowl of water. The ripest ones sink to the bottom, and the unripe (or less ripe) ones will stay on the surface. Discard the floaters.

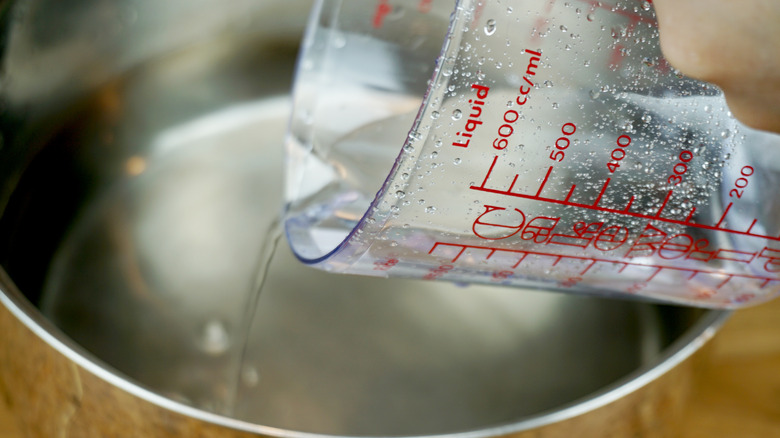

Using too much water

Making blueberry jam, jelly, and sauce consists of very basic ingredients, starting with the berries, the sugar, and some water. But how much water is too much water? Yes, you need enough so that your berries can cook down slowly, but too much water dilutes the blueberry flavor. On the other hand, if you use too little in cooking and your berries burn or aren't finished cooking, adding more water weakens the flavor, too. You're looking for the Goldilocks amount of water: not too little, not too much — just right.

The best course of action is to follow the recipe you've selected. Because water evaporates more quickly at higher altitudes, some recipe developers list a range of amounts to accommodate bakers and cooks in different regions. You'll need less water to get the job done at sea level than you will at 10,000 feet. If a range of water amounts is listed, start with the lowest amount and add more if necessary.

Forgetting to thicken

In a gooey fruit pie, the sauce that envelops the berries is one of the best parts. That flaky crust might be perfect, and the berries sweet and juicy, but if you slice into a pie and watery liquid leaks out across your plate, it's clear you've made one of the major mistakes you can make when cooking blueberries: forgetting to thicken. Even pies made with frozen blueberries need to have some sort of starch to prevent the center from oozing out and soaking the crust.

Recipes that rely on berries to produce a jammy, rich filling (like traditional pies, hand pies, and even toaster pastries) need to include a thickening agent. Flavorless options such as tapioca, arrowroot, and cornstarch soak up excess water molecules when they are heated. This chemical action is what delivers a luscious gel with pockets of whole fruit suspended inside it. But mind your cooking time and heat: When thickeners are cooked for too long at too high of a heat, the reaction can reverse, causing the starch to release the liquid.

Ignoring spices and herbs

Balanced tastes most clearly reflect perfection in a dish. Whether you like your blueberries bold and packed with flavor or dancing slowly with more subtlety, it is important to carefully incorporate spices and herbs, both fresh and dried. These elements add interest that makes a humdrum dish stand out.

Spices and herbs also work hard to prop up not-so-perfect fruit — the blandest blueberries get a boost when combined with certain spices and herbs. Traditional combinations like mint and basil are common, but it's okay to sample flavors from across the globe. Cardamom, cinnamon, and even chipotle chili have a place snuggled up next to blueberries, as do unexpected floral touches such as lavender and rose. Whatever spices and herbs you choose, remember that the dried and fresh versions are different and can offer layers of flavor. Fresh herbs work well as a finishing touch, and dried herbs and spices are best added when cooking is underway.

Improperly storing blueberries

If you've already figured out how to test for the longest-lasting berries at the store, don't sink the ship by storing your blueberries improperly. Some people bring their berries home and immediately rinse them, popping them in an airtight container. While that works wonders for raspberries, washing and sealing them in glass can spell disaster for blueberries. Blueberries prefer good airflow and no moisture. If the fruit sealed in a glass jar is not absolutely dry, mold quickly develops.

The best way to store your blueberries is in the container they came in. If they seem damp, add a paper towel to absorb any excess moisture, and keep them in the coldest part of the refrigerator. If you have a fruit drawer, blueberries do well in there; just keep the humidity level low, and they will stay cold and fresh. There's no need to wash the blueberries before you store them unless you plan to freeze them. If that's the case, wash and prep your berries, drying them thoroughly, then place them in a zip-top freezer bag. Properly sealed, blueberries stay delicious in the freezer for six months.

Ignoring savory pairiings

Yes, blueberries are a fruit, but so are tomatoes, cucumbers, and zucchini (botanically), and those are used in savory foods. The flavor of a perfectly ripe, fresh blueberry pairs beautifully with savory meals that include pork, wild game, beef, and chicken. Blueberries play well in marinades and are a featured ingredient in many shrubs, a beverage that dances the delicate line between sweet and savory.

So how do you start experimenting with blueberries in savory dishes? It's easy to toss a handful of berries into a marinade or add them to a savory pan sauce (think black pepper and a little balsamic vinegar reduced, finished with butter, and drizzled over a perfectly cooked steak). Include blueberries in your next barbecue sauce, add blueberry jam to a vinaigrette, or start your own shrub with blueberries that aren't quite so flavorful. Blueberries can also be added to savory baked goods (think thyme scones or rosemary focaccia) for an interesting twist.

Using out-of-season blueberries

Just because you can get a pint of blueberries when there's a foot of snow on the ground doesn't mean you should. Variety is the spice of life, certainly, and it's great to have a diet with a rainbow of fruits and vegetables, but there are few things more flavorless (and culinarily useless, frankly) than an out-of-season blueberry. They tend to be smaller, mealy, and tasteless.

If you are craving blueberries and nothing else will do, you have options. Frozen blueberries are usually picked at the height of the season and flash frozen to preserve the taste and texture; these are an option year-round and work well in almost every application. If you want to go all in, consider holding off on satisfying your blueberry craving for now and looking ahead to the summer when the fruit is fresh and delicious and can be purchased on sale in large amounts and frozen for use in the colder months. This culinary long game will pay off dividends in January when you slice into the mouthwatering pie made with berries you preserved from the previous summer.

Not macerating blueberries

Macerating is the specific culinary term used for letting fruit sit for a while in sugar, liquor, or some other fluid (even its own juice). This process draws moisture from the blueberries, flavoring the liquid, while the liquid seeps into the fruit and flavors it. This process also softens the fruit, like cooking without applying heat. It's like a beautiful cycle of flavor building that can only make your dishes taste better.

Most fruit needs to be cut into chunks for maceration, but blueberries don't need anything other than the standard prep of washing, drying, and removing any stems or detritus. The simplest method is to toss berries in sugar and let them sit at room temperature for at least 30 minutes. You can use the thick sweet syrup separate from the fruit or toss the whole fruit and syrup into whatever you're cooking. Macerating also extends the life of berries on their way out; cover the fruit in sugar, cover the container tightly, and place it in the fridge. Berries will be good for another four days.

Overmixing blueberries in baked goods

Nothing beats the luscious, fruity burst of flavor when biting into the perfect blueberry muffin. An intact blueberry provides moisture and a different texture that contrasts nicely with whatever baked good you're enjoying. Don't ruin the dining experience by overmixing your blueberries into your baked goods.

Overmixing blueberries, especially vigorously and with disregard for the delicacy of exquisitely ripe fruit, can cause them to break and bleed. Not only does this ruin the juicy surprise, but it also causes lighter-colored cakes, pancakes, and muffins to turn a ghastly shade of greyish-purply blue. The burst berries can also make the area around them soggy, resulting in an overly wet mouthful of cake. Avoid this by gently folding blueberries into the batter until they are completely covered (usually the last step before baking). Use a spatula or wooden spoon instead of a whisk to avoid getting berries stuck between the wire folds and breaking.

Not using lemon juice

Lemon juice is a miracle addition that is the secret to better-tasting food, and anything made with blueberries is no exception. Whether savory or sweet, a bland dish made by an inexperienced cook is often over salted in a blind attempt to make it taste of something, but what is missing is probably the bright acidic jolt lemon provides. Lemon (and any other kind of acid, really) makes food taste more deeply of itself by activating the saliva glands; the sour flavor is especially good at bringing out the sweetness of blueberries that may have traveled long distances or may not be 100% ripe. Lemon juice can also preserve the color of blueberries — no more murky blueish haze dotting your pancakes or muffins.

So when do you add juice, and when is zest the best? Both add a bright flourish to your dish, but juice is best when additional liquid won't matter (i.e., in sauces and marinades), while zest works well in baked goods where the liquid-to-dry ingredient ratio is important.

Skipping the tossing in flour

If you've experienced the heartache of cutting into a blueberry limoncello drizzle cake only to find a soggy layer of weeping blueberry settled into the bottom of your cake pan, you're not alone. Blueberries have some heft to them, a weight that can become more pronounced as the lighter batter rises in the heat of the oven.

Yes, you can layer the blueberries and the batter, but combining this technique with one other method guarantees even distribution: Take the simple step of coating your blueberries in flour before you add them to the batter. Don't add additional flour — that might throw off the ratios of dry to wet ingredients and cause other problems. Simply mix your dry ingredients together, then remove a tablespoon or two of flour and toss it with the blueberries. When it's time to fold in the berries, add the berries (and any stray flour) and mix them gently through your batter. This method works well for thin batters, particularly when you lay down some batter (with no blueberries in it) into the pan first.

Using metal utensils instead of wood

There has long been a rule that metal utensils and acidic foods don't mix. While some people swear there is not a difference, others have noted a strange color or off flavor that occurs when blueberries are cooked in aluminum pots and stirred with metal utensils. Why take the chance?

Unless you use ceramic cookware, there's no getting around cooking your blueberries in a metal pot. Use a high-quality stainless steel pot and take care to not overcook your berries on too-high heat. Opt for enameled cast-iron if you're making recipes with long cooking times like jams or jellies. Wherever possible, use non-reactive kitchen utensils made of wood or silicone; metal spoons and spatulas may be made of cheaper materials that are more likely to react with the acid in the berries. If you do opt for wood utensils, use spoons dedicated to sweet foods or those that have been properly cleaned to remove food odor and tastes.