Secrets Of Bologna You'll Wish You Knew Sooner

Most of us know the word bologna has two different meanings and pronunciations. Capitalized and pronounced with its original pronunciation, "bo-LONE-ya," it refers to a bustling city in central Italy known for its medieval architecture, thousand-year-old university, and sumptuous food culture, which features rich meat sauces over pasta as well as tortellini, a local specialty.

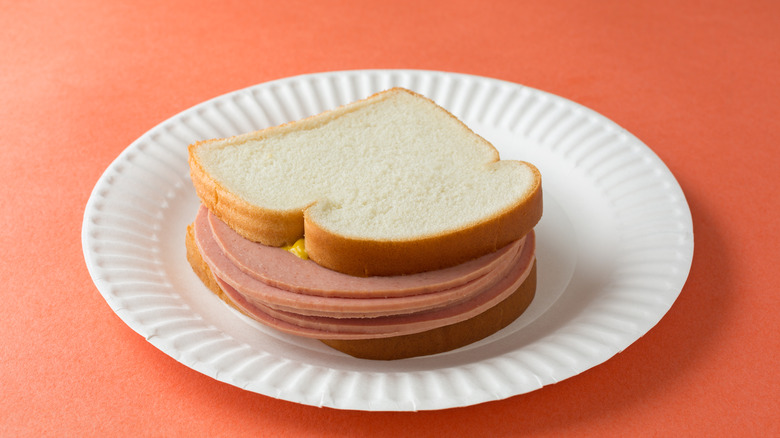

But, pronounced "buh-LONE-ee," the word means something very different: a pink processed lunch meat, usually found in thin round slices between two slices of squishy industrial white bread. For some, bologna sandwiches are a beloved taste of childhood that evoke memories of sack lunches lovingly packed by Mom and carefree lunch breaks on an elementary school playground. For others, they're a sodium- and nitrate-filled nightmare that deserves to stay buried in the past. Whatever your feelings, there's no denying bologna is a deeply entrenched part of American food culture with an interesting story to tell.

Bologna is a close relative of mortadella

Yes, bologna, the cheap lunch meat, does indeed have a relationship with Bologna, the sophisticated Italian city. But, the cold cut as we know it was historically unknown in Bologna. Instead, the city was known for a similar sausage, mortadella, which was eaten throughout antiquity in Italy but became so closely associated with Bologna and the surrounding areas that it was codified in 1661 and was eventually granted a Protected Geographical Indication by the European Union in 1998.

When the sausage was introduced to the U.S. by Italian and German immigrants, it gradually morphed into the bologna we know today, which differs from mortadella in several key ways. While mortadella is multi-textured — it must contain visible cubes of pork fat along with finely ground pork, and can contain add-ins such as pistachios and olives, bologna, according to U.S. government regulations, cannot contain any visible chunks of fat. While mortadella is always made from pork, American bologna can contain beef, chicken, or turkey as well. And, while mortadella was historically food for the rich (since grinding the meat to the required fine texture in the days before food processors was a long and labor-intensive process), American bologna was always made with an eye to affordability.

Why is bologna pronounced baloney?

One of the most enduring mysteries for bologna lovers, besides the question of exactly what's in it, is the question of why we pronounce it the way we do — that is, how did bologna come to be pronounced (and sometimes spelled) "baloney" by American diners?

A big part of the reason is the diverse range of people who were introduced to it when Italian and German immigrants first brought it to the U.S. Anyone who's studied a foreign language knows that common words and sounds in other languages can be bafflingly difficult for native English speakers to pronounce correctly, and vice versa — foreign accents are just the influence of the speaker's first language on their English. Thus, when residents of New York, where bologna was first introduced, encountered the treat, they struggled with its original Italian pronunciation, calling it "baloney" or even "blarney" instead — and the new, easier-for-them pronunciation stuck.

Bologna's ingredients aren't as sketchy as you think

Among the reasons bologna gets a bad rap among some foodies is its reputation as a repository for mystery meat: Since it's tough to visually identify any of the ingredients in a slice of bologna, it's all too easy to imagine it as a shady mixture of who-knows-what gussied up with a heavy dose of artificial flavorings and preservatives. And, there's good reason for these suspicions: Historically, bologna was made from the cheapest possible ingredients, and these were often organ meats, which some would be unwilling to eat on their own.

You'll be relieved to know, however, that this is no longer the case. Organ meat is rarely used in modern bologna, except for in a few traditional varieties from Pennsylvania that include liver or other organs as part of their original recipes. And, while organ meat has a long and honorable history in sausage making (cleaned intestines are still used as casings for many varieties, and organ-meat-forward sausages such as liverwurst continue to have loyal fans), organ meats must be disclosed on ingredient lists, so it's easy to avoid them if you prefer.

There's more than one type of bologna

The world of bologna is more varied than you may think — and if your only experience with it was through sandwiches featuring your mom's favorite brand of supermarket slices, you may be pleasantly surprised to discover that bologna can come in a wide range of different shapes, textures, and flavor profiles.

For instance, German sausage makers also embraced bologna, and their signature variety, called Fleischwurst in German and garlic bologna or garlic ring bologna in the U.S., features (surprise) a strong garlic flavor. Polony, a bologna version popular in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries including Australia and South Africa, is a smoked sausage featuring a bright orange or red skin. Lebanon bologna, a specialty of Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, is a smoky, tart sausage with a firmer texture than other bologna varieties. Rag bologna, a specialty of Tennessee, is a softer, saltier variant that comes wrapped in cloth, and ring bologna, as its name implies, is a slender, curved sausage link often sliced and served on crackers.

The Oscar Mayer bologna ad was shot in one take

The most effective ads not only catch the public's attention, but indelibly link a brand and a product in the public mind. A textbook example of an ad that achieved this mission is the classic 1973 Oscar Mayer bologna ad: It consisted simply of a curly-haired 4-year-old boy in overalls holding half a bologna sandwich while singing the now-famous jingle starting "My bologna has a first name, it's O-S-C-A-R..."

The ad — and its earworm of a jingle — did exactly what they were designed to do. But oddly enough, the ad that aired was not the one Oscar Mayer marketers envisioned. Instead, they'd planned to feature a montage of several children in different activities, all singing snippets of the song. But, as the shooting for the ad concluded, the director noted that it was still light out and there was time to shoot more footage. He asked the children if any of them knew the song well enough to sing it solo all the way through. Four-year-old Andy Lambros volunteered – and sang the song perfectly in just one take. When Jerry Ringlien, Oscar Mayer's V.P. of marketing at the time, reviewed all the footage the next day, the boy's impromptu solo jumped out at him. "I looked at it one time, and I said, 'That's it, that's the commercial,'" he recalled (via YouTube).

A prison's bologna-heavy meal plan received multiple complaints

Some picky children may think nothing of having a bologna sandwich every day, and may indeed prefer a familiar, safe, and monotonous menu to the risk of facing strange new foods they might not like. For hungry, food-loving adults, though, the idea of facing a basic bologna sandwich every day may seem a bit infantilizing, not to mention boring and offering questionable nutritional value.

But, for inmates at Dakota County Jail in Minnesota in the 2000s, bologna sandwiches — and only bologna sandwiches — were their dinner, seven days a week, weekends and holidays included. Each evening, each inmate got two turkey bologna sandwiches and a small portion of fruit. It was not only excruciatingly boring but left inmates hungry, especially on weekends, when they were served brunch at 10 am and didn't get their bologna dinner until 8 pm. In written complaints, inmates protested "sandwich meat (1 slice) so thin you could read the newspaper through it" and "civil rights that are being violated," according to the Twin Cities Pioneer Press. Prison officials defended the menu as providing sufficient nutrition while saving money — but the Twin Cities Pioneer Press noted that inmates in other Minnesota jails enjoyed two hot meals, such as hamburgers and meatloaf, each day.

Fried bologna sandwiches have gone gourmet

Fried bologna sandwiches have long been an under-the-radar favorite of thrifty home cooks. They have all the familiarity, convenience, and affordability of basic bologna sandwiches with a bit more punch and polish: fried bologna, with its sizzling meat and crispy edges, offers some of the same smoky, fatty vibes as bacon, but with a lot less work.

Tasty as they are, however, fried bologna sandwiches have never been seen as high-class food — until recently. Nostalgic chefs and restaurateurs, some striving to pay tribute to their childhood memories, have embraced the humble fried bologna sandwich and elevated it into a showcase menu item. At Gertie's Bar in Nashville, for example, chef Matt Bolus smokes a whole bologna over wood, slices it thin, and serves it stacked high on a sandwich topped with whiskey-infused slaw. Chef Craig Deihl of Hello, Sailor in Cornelius, North Carolina, serves smoked bologna slices in sandwiches , then fried until crispy. During tomato season, he features it in his version of a BLT, in which he subs out bacon for bologna.

Why does baloney mean nonsense?

Bologna, as we know, has two pronunciations:"bo-LONE-ya," the original Italian pronunciation used to refer to the city of that name, and "bu-LONE-ee," the Americanized pronunciation used to refer to the cold cut. And then, there's the alternate spelling, "baloney," used to refer to both the cold cut and to spurious or nonsensical information.

So, how did a word for lunch meat come to be equated with poor-quality information? Written records of the word baloney used with humorous connotations emerged as early as the 1870s, and by the 1920s the word was frequently used to refer to dim or graceless people as well as nonsense. However, the link between the sausage and this meaning remains unclear. One theory is this usage originated in the stockyards of Chicago, where old bulls were called bolognas because their meat was too tough to eat in any other form. And some etymologists don't even believe that baloney is related to bologna. Instead, they hypothesize it may come from the similar-sounding Romani word for testicles, peloné, or from balonie, a word meaning "nonsense" in Polari, a specialized form of slang used by British theater and circus communities.

Bologna sandwiches have fallen from favor

Ever since bologna took root in U.S. food culture, Americans have had a love-hate relationship with it. Because it was cheap and easily obtainable, it became a staple in many homes during the Great Depression. But, even as hungry families ate it, they knew of its reputation as a shoddily made concoction loaded with questionable organ meats.

This reputation persisted well after the Depression. This all changed after the Oscar Mayer Company launched its then-viral ad for its bologna, (featuring the aforementioned cheerful little boy singing the virtues of the product). While bologna was already a top-seller for Oscar Mayer before the ad was launched, it cemented the product in the public mind as a wholesome and desirable part of childhood, and bologna sandwiches kept their place of honor in school sack lunches. But, by the 2000s, the pendulum swung the other way, and concerned parents dropped dowdy (and nutritionally questionable) bologna sandwiches for bento boxes filled with carved fruit and vegetables.

Bologna isn't just for sandwiches

Yet another reason bologna doesn't get taken very seriously is because it's often associated with just one thing: sandwiches. And, despite bologna sandwiches being reimagined as Instagram-worthy artisanal creations by high-end chefs, at the end of the day, a sandwich is still a sandwich. Much as we love them, few of us want to eat them all the time.

Bologna, however, is much more versatile than many may think, and just like ham or other flavorful cured meats, can be used as either an accent or a star ingredient in a range of dishes besides sandwiches. For instance, you can cut ring bologna into cubes and toss it into fried rice. Slice it into thin strips and toss with same-sized strips of cheese, minced pickles, and a pickle-brine vinaigrette to make a hearty lunch salad or light supper. Toss some cubes of bologna into a pasta salad for a fun picnic dish. And, ground and mixed with minced celery, onion, egg, mayo, and sweet pickle relish, bologna becomes a flavorful spread for crackers (or yes, a sandwich filling.)

150-foot bologna sandwich was made for charity

We all know what a bologna sandwich is supposed to look like: Two slices of white bread. A swipe of mayo or Miracle Whip. A slice or two of bologna. And, if you're feeling fancy, maybe a slice of cheese or a bit of lettuce. Stick it in a plastic bag (or wrap it in waxed paper if you want to go old school) and your lunch is ready to go.

But, this is not how Chef Brian Peffley made his sandwich for the Lebanon Area Fair in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. Instead of typical supermarket bologna, he used a regional specialty, Lebanon bologna, a spicier and tangier version. And critically, because he was charged with making the world's largest Lebanon bologna sandwich, he fashioned together 90 French loaves at 2-1/2-foot long each out of 250 pounds of flour. After putting them end to end, he filled them with 1200 slices of locally made all-beef Lebanon bologna and 600 slices of provolone cheese. The project was intended as a charity fundraiser: Sponsors paid $100 per foot for the sandwich, raising $15,000 for a local charity that provides clothing, counseling, food, and shelter to needy area residents. The sandwich was later cut into 900 slices, served at no charge to fairgoers.