A Chef's Life: Vivian Howard On Slathers, Snobs And Muscadine

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Chef and TV host Vivian Howard's friendly, introspective and thoroughly enjoyable PBS series, A Chef's Life, won the 2016 James Beard Award for Outstanding TV Personality. It will presumably make a great addition to her Peabody Award, her Emmy, her slew of culinary accolades and her pile of JBF Best Chef Southeast nominations.

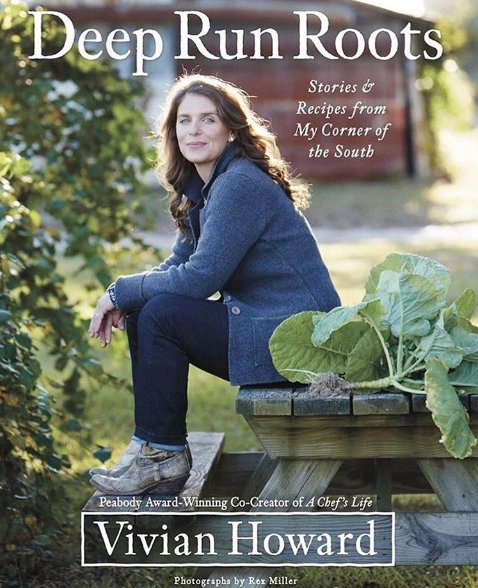

While gearing up for her fourth season, which premieres in September, Howard launched a line of slathering sauces and rubs for Williams-Sonoma and is working tirelessly on her first cookbook, Deep Run Roots, out in October. With prime fruit-preserving season at her Kinston, North Carolina, restaurant Chef & the Farmer in full swing — an essential step in sauce-making — it's safe to say she has a full plate.

We spoke with Howard about finding purpose in her Southern roots (and why you should never try to modify your accent), the fall of food snobbery, the rebirth of modern farming and how to write a cookbook that really stands out.

When you first came to New York City from North Carolina to work in advertising, did you ever imagine that Southern cuisine would be one of America's most popular restaurant genres? What does it say about America's food culture?

No, I was trying to escape Southern food and was relatively ashamed of it at the time, so the fact that it's become what people consider our one indigenous cuisine and celebrated in the way that it is has been big. I think for so long our country looked outward for inspiration and for all things excellent and quality-driven, and I think that our interest in Southern food — the way we are able to exalt it — is an example of our acceptance of ourselves as a country with a worthy food culture and history. I think it's deeper than just understanding that Southern food can be balanced and tasty and beautiful; it says more about how we see ourselves.

When you transitioned into the restaurant industry, what did you find was the greatest asset of a background in Southern food?

When I moved to New York, I wanted to be a journalist. I worked in advertising, then as a server in a restaurant called Voyage, where the focus, by the weirdest coincidence in the world, was Southern food via Africa. This was in 2000, way before anyone cared about Southern food, way before I cared about Southern food. My connection to the food I grew up eating, coupled with my enthusiasm for the chef I was working for, really changed the way I viewed what I ate where I grew up, and the way I valued myself. When I first moved to New York, I was not quite comfortable with my roots. I didn't want people to know I was from a tobacco farm in eastern North Carolina and did everything I could to prevent them from finding out. I didn't lie about it, but I didn't share my background and I altered my accent to the point where people asked me if I was from New Zealand. Working at Voyage gave me a sense that maybe I was undervaluing where I came from. I had to move to New York City to realize it.

Are the lessons in cuisine and agriculture taught by older folks in the South effectively being passed down to younger generations, who are more interested than ever in food but not necessarily in growing or cooking it?

Unfortunately, I don't. I think that my parents' generation was really the last generation that grew up slaughtering hogs and preserving meat to make sure there was food to eat in the winter. My parents were so happy they didn't have to do that anymore that they didn't pass those skills on to us, so my generation is really detached from it. Now you have this younger generation who's very interested in eating those things, but don't understand the survival mechanisms of why they're there.

In terms of agriculture, we have a major crisis on our hands. Something like 78 percent of farmers are over the age of 65, but we have a major farmer shortage. While we're all obsessed with the quality of ingredients, farmers' markets, eating at creative restaurants, people aren't necessarily jazzed about doing that kind of work, and I don't know what the solution is. We recently did some work with an incubator farm, which is this very smart concept of teaching people how to farm without a huge plot of land. So many farms historically were handed down from generation to generation, and that's not the situation most people are in nowadays.

I saw a video you did with Le Creuset (above) where you admitted struggling to pronounce "Le Creuset." I've noticed that people will go so far as to avoiding ordering something they're not sure how to say. Any advice to those who stumble with "arugula" or "andouille"? Are we dealing with a snobbery/shame situation here?

I hate to think that someone is not going to eat something delicious because of that, but I definitely feel you! For so long I was that person, but I think that in a restaurant situation you'll find, particularly nowadays, that your server really just wants you to have a nice time, and if you're uncertain about how to pronounce something, you're much better struggling to pronounce it and then enjoying it.

In my own experience with TV and situations like that Le Creuset video, if you're able to show some vulnerability, people can relate to you more. We should never be afraid to seem ignorant, because we all are to some extent. I think we're past the age of wine snobbery when sommeliers and servers would look down at a diners, so I encourage people to order what they want. People in our region love sweet wine, so we have all kinds of muscadine on the menu. I wanted to prove myself originally, so we refused to serve it and encouraged people to get something else. A few years ago, we realized it's really not about us. It's about the diner having a nice time, and if they want it, we should have it for them; otherwise they'll drink tea or water, and that's not in our best interest. I think restaurateurs have come to realize that hospitality is about making the diner feel good.

Do you think the intensity of food media today coming at you from everywhere intimidates or invites more people, and how does that intensity influence your own approach to food media?

I think it invites more people. It's important for food media to be varied — there's so much of it out there right now that unless you have a distinct voice, it all kind of gets lost in the shuffle. For me, I struggle with that because I understand that in order to continue doing the stuff I want to do, making cookbooks and this very unusual show on PBS, turning people on to my line of fruit-based meat sauces, that I have to continue to push my own food-media person. I so badly don't want to become a caricature of myself and oversaturate the market with Vivian Howard. The fact is that people used to go to movies and art museums and concerts and theaters, and now people go to restaurants for the same kind of culture and performance. We're all still trying to wrap our minds around it.

Hey, let's talk fruit-based meat sauces! How did you come to work with Williams-Sonoma?

It's a strange story — we were talking to WS about a partnership for our show for a long time (it's on PBS, so we had to raise funds to make it). It became clear that it wasn't going to happen, but I appreciated their time, so I sent one of their brand people the blueberry sauce we'd been bottling, along with with a thank-you note. A few weeks later, I got a thank-you note from their food buyer, who said, "We really love this sauce, and we'd love to carry it, but in order to do that we need a full line of products. Have you ever thought about doing others?" And we had, because I'm really passionate about fruit preservation. We do a lot of that during the summer here, so we can use those fruits in the fall, winter and early spring in savory applications, so I said, "Yeah, I've got lots of ideas!" Like with everything else, we do jumped in full-body and offered the three rubs we use at our restaurants, which was relatively easy to do. The sauces were more of a process.

Were there any flavors that didn't make the cut?

Yes. I'm a big fan of pepper jelly, and we wanted to do one with an acid edge, but we were worried that the overt spice might turn people off. We were also concerned about doing fruit sauces because they have such a bad reputation in general. Sometimes they're just so cloyingly sweet, which is what people have come to expect. The whole premise was on the chopping block for a long time.

Is it okay that I spread it on sandwiches like mustard?

Absolutely — I think the slather is great on a ham sandwich! Sometimes at the restaurant we'll add Dijon mustard to it and serve it with trout. It's incredible versatile. It's amazing to me that for so long we've made these preserves, apple butter in particular, but rarely add anything to balance it and make it into a real condiment.

The fruit gives the sauce a clingy quality without adding any extra sweetness. How did you strike that balance of sweet, fruity and savory?

Substituting some of the sugar you'd find in a sauce with actual fruit adds really nice body and a nuanced acidity that you don't get from straight vinegar or citrus. We found that coupled with additional acidity like cider or rice wine or sherry vinegar, it really accentuates the fruit in a way that's kind of surprising.

And even with all that, you said on The Chew that your kids won't eat them.

Yeah, I hope they come around. My son and I made ribs last week with the apple slather, and he ate them. We make barbecue chicken a lot with the blueberry sauce, and my daughter goes, "Oh no, the blueberry!" She's tough when it comes to anything that's not anything I actually want her to eat.

You have a cookbook in the works that I can't wait to see. I saw you holding up the uncorrected proof on Instagram with a super-excited look! How's it going?

It was very difficult to figure out exactly what I wanted it to be and what I wanted to say. I want the book to be more than a chef's cookbook. I want it to represent my region and give the people here a sense of pride in their place, and make sure I'm proposing that Southern food is not one thing but multiple things. The book is half-narrative. Our region has a cuisine that's as varied and interesting as any in the world, so if you're going to claim that, you have to do it right, and that took a while. I'm arguing that the food of eastern North Carolina deserves a voice in the cuisine canon of the world. It's not a big place, and we don't have a million dishes under our belts, but neither does Provence or Tuscany — it's just some characteristics developed over a period of time based on the population and terrain, and I'm using the book to argue all those things.