Can You Trademark A Grain Of Rice?

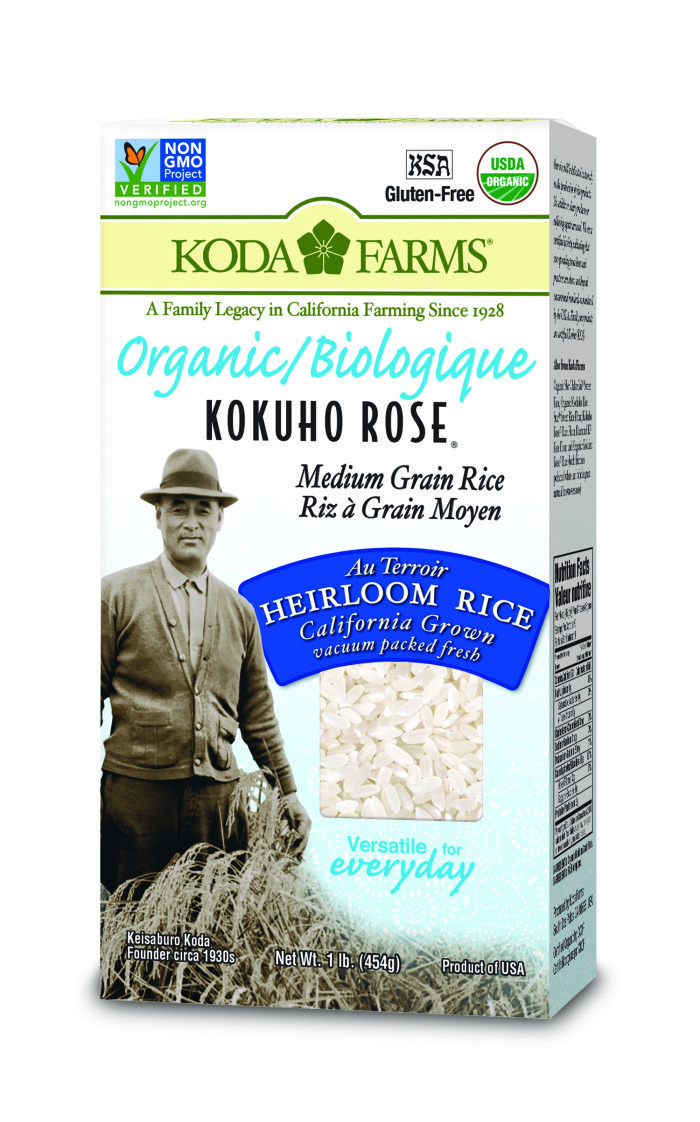

The story of the perfect grain of rice began with a dream. At the start of the 20th century, Keisaburo Koda left a successful career as a school principal in Japan to seek his fortune in the United States. Like many Japanese men, he tried his luck in the oil fields of California before setting up a more permanent business. After World War I, Koda moved his family to Dos Palos, located at the southern tip of California's fertile central valley, to start a farm.

It was a dark time in California's history as racist laws like the Alien Land Law of 1913 prevented anyone ineligible for citizenship from owning land. Koda listed his two young American-born sons as stockholders in his new farm, which grew mostly rice. His dream was to get his California farm to produce a delicious grain of rice similar to the premium rice varieties grown in Japan. An innovator from the start, he was one of the first farmers to use low-flying airplanes to sow the seeds on the rice paddy, and his farm prospered between the wars. However, after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Koda family, along with most of California's Japanese population, was cruelly relocated to an internment camp and lost most of their farmland.

After the war, the Kodas essentially had to start over. The new generation, consisting of brothers Bill and Ed Koda, hired a rice breeder named Arthur Hughes Williams to develop a unique seed program. He spliced together a short-grain Japanese strain with a long-grain Middle Eastern strain to achieve a perfectly balanced medium grain. The strand, then called KR55, was later named Kokuho Rose, which translates to "nation's treasure" and was trademarked in 1962.

"The trademark was designed by our grandfather because he wanted to be able to handle the rice from growing the seed to having the packaged rice ready for consumers," says Ross Koda, grandson of Keisaburo and current president of Koda Farms. Ross and his sister Robin still run the family farm and uphold their grandfather's mission.

When Kokuho Rose hit the market in 1962, demand exploded, and Koda Farms couldn't keep up. "As the demand became more than the supply, our main rice broker asked if he could take some of the seed up the Sacramento valley and have farmers grow it there." The Nomura company produces most of the commercially available Kokuho Rose rice and pays a royalty to Koda Farms for use of the seed and name.

There are seven current trademarks on file with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office held by the Koda family. Three of them are stylized drawings of Japanese characters used on packages, and the trademark for the word "Kokuho" is listed as having first been used in commerce on March 1, 1950.

The difference between the rice grown at Koda Farms and Nomura's widely available rice is that "Nomura's is a descendent of the original heirloom Kokuho Rose," Ross Koda says. "When you're growing an older type of variety of rice, an heirloom variety like we have, for our KR55 variety, our target production of both conventional and organic rice is 5,000 pounds per acre." A more profitable commercial production target is "about 9,000 pounds per acre," he says. California has a very successful and very good rice-breeding program for improvement, resulting in products like "calrose" and "California basmati," but Ross Koda says the focus is on volume, whereas growing Kokuho Rose requires "focus on the taste, texture and improving qualities versus growing the variety that's gonna give us the biggest yield."

"We want to do something special and offer something a bit different to our customer," says Ross Koda. And rice aficionados agree. You can find Koda Farms heirloom Kokuho Rose rice served at the hip Los Angeles cafe Sqirl, in the heart of Silver Lake. There's also Onigilly in San Francisco, which makes its onigiri (Japanese rice balls) out of Koda Farms' rice.

And it is very different indeed. You don't have to be a sushi chef to make perfect rice. If you've seen the film Jiro Dream of Sushi, you know that chefs spend years perfecting sticky rice, but Kokuho Rose cooks into perfect ovals that stick together in just the right way, even without a rice cooker. Just add one cup of rice and one cup of water to a 1.5- to 2-quart saucepan, cover and bring to a boil. As soon as the lid starts to shake, after about five minutes, turn the heat down to a simmer and cook for 15 minutes. Then let the rice rest for another five minutes off the stove but still covered. The key is to keep the cover on through the whole process. Fluff the rice with a wooden spoon, add a tiny dash of rice vinegar, a pinch of sugar and salt and you've got the perfect bowl of rice.

Seeds are generally given heirloom designation after 50 years of cultivation and when the process is still done on small farms using traditional methods, so you can only get pure heirloom Kokuho Rose from the original KR55 strain at Koda Farms. According to the Koda Farms website, it "does not thrive outside of a thirty mile radius of our farm — the essence of 'au terroir.'" Koda Farms' commitment to preserving the heritage grain is commendable in a climate when companies like Monsanto are pressuring farmers into buying mass-produced seed.

The future, though, could depend on climate. California is experiencing a terrible drought at the moment, and Koda Farms is feeling the effects. "We're going to get by this year with the acreage projection that we wanted," says Ross Koda, "but next year is really up in the air."