When You Wish Upon A Baby Anchovy

In June, Food Republic is counting the many reasons to love Asian food in America right now. Here's one of them.

It was late June of 1991, and everything was moist. The chair-joined-desks. The beige, mosaic hallways. Even the brown paper bag–covered textbooks were damp, ready for a three-month respite from the sticky children. The teachers had given up on lesson plans a week ago, instead throwing in another VHS tape of Voyage of the Mimi and silently mouthing the countdown to the final ten seconds of each period. And we, the students of Travell Elementary School, were collectively buzzing with excitement.

But on this very last day of third grade, no one was happier than me in all of America. For the first time in my American life, I was going to be normal. I wouldn't be seen as the garlic-smelling, slanty-eyed "Chinese girl" who came to school in brightly colored Benetton shirts all the time. I was going to be accepted, even embraced, as one of the nonthreatening blonde girls named Jennifer or Katie who got to attend Girl Scouts on Sundays, call their friends' parents by their first names and wear shoes inside their homes. Yes, classmates, I thought, I am just like you because this summer, I am going to Disney World.

My family took a trip every summer for two weeks. It didn't matter if we were going to St. Louis to visit relatives or to the Grand Canyon to "learn about America" — our packing list was as regimented and orderly as our daily schedules, which for me always included hour-long piano practices, additional Kumon math homework and Bible study before bed. Our family motto and the Korean way of life were one and the same: Do as you're told, and do it well.

My brother and I would bring our CD players, Game Boy and comic books. My dad would make sure he had his four premarked maps. And my mom would pack her rice cooker and a giant sack of rice. Now, a just-in-case rice cooker sounds pretty smart, especially if you hit some nasty rest stops or scary buffets along your route. But what accompanied the rice on this trip left prudence behind on our front steps in New Jersey. My hyper-organized, and apparently starving, mother would pack an entire Igloo cooler full of an assortment of homemade Korean banchan.

Each airtight Tupperware bin had to be individually wrapped in three plastic bags, to lock in not freshness but rather the intense smells that would otherwise take unwelcome residence in everything we wore, down to our socks and underwear, while inside the car. So with our toothbrushes, bathing suits and room-temperature cooler full of hundreds of tiny fish eyes and rotting sesame leaves packed into the station wagon, the Kyes were ready to hit the road.

At a Korean meal, you will almost always see rice, kimchi and a bunch of little side dishes called banchan. Unlike Western cuisines, Koreans don't mess around with "courses." The banchan set in front of you as you sit down are not appetizers or meant as an amuse-bouche. On the contrary, banchan is the backbone of the Korean table and meant to be eaten throughout the meal. Never underestimate the power of the tiny bowl of limp bean sprouts or its neighbor, the dish of humble black beans. Without these supporting players, a superstar like Korean BBQ would have no one to pass the ball to.

The name of the banchan game is preservation, and in order to achieve this, vegetables, beans, fish, meat and any other food are pickled, fermented, cured, salted and dried to achieve not only longevity but maximum flavor. Like many places in the world, Korea has short growing seasons and long, harsh winters, but that doesn't stop us from eating well 365 days a year. Koreans have perfected the art of preservation, kimchi being the stinking, shining king in the banchan landscape. We've learned that taking fresh cabbage in the summer, salting it, brining it, spicing it and then rotting it satisfies our demanding palates and appetites till the next harvest, not to mention also keeping us strong, healthy and beautiful.

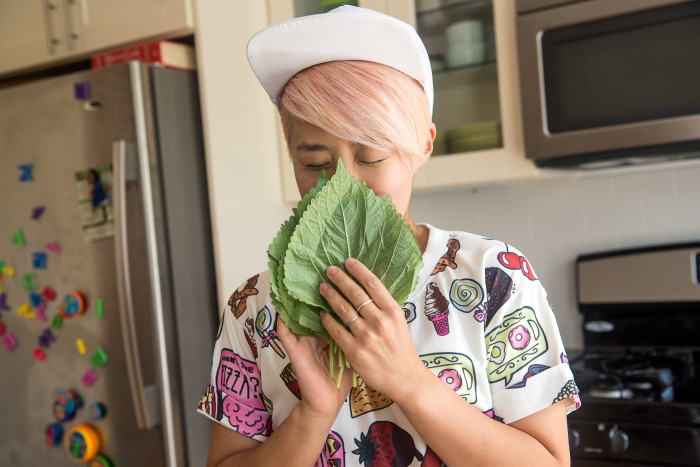

And while there is a deep history and much-studied philosophy on harmony and balance that is associated with banchan, for me it's simply the satisfaction of putting two different banchan in my mouth with some rice that brings order to my life. And sometimes, after a long day of greasy burgers and oily pizza, all I crave is the perfection of a bowl of hot white rice and my favorite banchan — pickled sesame-seed leaves called kkaenip jangajji.

♦♦♦

Serves 6-10

Koreans love to wrap things around rice, and this wrap packs a punch. It is a banchan that can be off-putting for some, since sesame leaves are part of the mint family and on their own have a bold herbaceous flavor. You can find them in all Korean and most Asian groceries, but be sure to look for the Korean sesame leaves rather than the Japanese shiso or perilla leaves — they have a different taste altogether.

35-40 sesame leaves, washed, stems trimmed

12 tablespoons soy sauce

1/2 teaspoon rice vinegar

1 teaspoon gochugaru (Korean chili powder)

2 cloves garlic, minced

2 tablespoons finely chopped chives

1. Thoroughly rinse sesame leaves under cold running water. Pat dry.

2. Mix together remaining ingredients in a bowl.

3. In a sealable glass container, lay down a spoonful of the soy-vinegar mixture. Place a dry sesame leaf on the mixture. Add another spoonful of the liquid and spread it on top of the leaf. Repeat this action till all the sesame leaves are stacked.

4. Seal the container and refrigerate for at least 24 hours. Eat with rice.

♦♦♦

During our 20-hour ride down to Mickey, my mom would open up her prized box of pungent treasures at every rest stop — without hesitation or shame. She'd roll out our bamboo mat on any patch of grass next to parked semi-trucks and casually reveal braised beef and eggs (janjorim), seasoned seaweed (doljaban muchim) and seasoned bracken fern stems (gosari namul).

Once the "table" was set, we'd plop down while my mom squatted next to her rice cooker to paddle out individual portions of still-warm white rice on disposable paper plates with little flowers on them. And just as we did at home with every meal, my dad would demand we hold hands, close our eyes and pray for our food. I'd look over my shoulder with one eye open and count how many people would point at us and stare.

Embarrassed at how different we were, I inhaled these all-too-public meals and pretended not to enjoy the alien dishes. My mom would scold me and tell me to slow down. As I quickly gulped down fish bones, I studied with great envy the white families happily sitting around the picnic tables dipping their Happy Meal nubs of meat into prepackaged sauces. My mom would say she'd rather starve than eat that kind of "American food." Before I bolted up from the mat, she'd hand me a plastic cup of roasted-corn tea to wash down the intensely salty, spicy, appropriately sweet flavors that made you sit up straight after being slumped over in a cramped car for hours.

Once we got to Disney World, our meals got a bit more complicated. Even with "authentic" restaurants galore in Epcot Center, there was no way my mom was going to eat a piece of shrimp from the hibachi chefs of the "Japan" area. And since there was no outside food allowed in the parks, my mom got creative: There were no eating restrictions in the vast parking lots outside the gates blasting "It's a Small World."

So while my brother and I were running from Space Mountain to the Mad Tea Cups, deliriously foaming at the mouth like rabid dogs, my mom would leave the park an hour before mealtime, head back to our hotel room and mull over her creations — this time storing them in even more compact, purse-friendly Ziploc baggies. And since this was literally a dine-and-dash type situation for my brother and me (we'd have shoved food into our mouths while running in place), my mom would make her life easier by bring the less fussy banchan, like roasted seaweed sheets (easily wrappable in rice) and stir-fried anchovies (myulchi bokkeum).

Serves 4-6

Dried anchovies are ubiquitous in Korean cuisine. Not only are they eaten as banchan, like in this recipe, but they are also constantly used as part of a soup broth that begins most stews and soups. This recipe calls for small dried anchovies (maybe a centimeter or two long). In a pinch, you can use the slightly larger (inch-long) anchovies more commonly found in Asian markets.

2 teaspoons canola oil

2 teaspoons gochujang

1 teaspoon soy sauce

3 tablespoons rice wine

2 tablespoons water

2 teaspoons sugar

2-3 garlic cloves, thinly sliced

1 cup of small dried anchovies

1 teaspoon sesame oil

1 teaspoon sesame seeds

1. Heat a large pan on medium-high heat and add canola oil, gochujang, soy sauce, rice wine, water, sugar and garlic. Mix in the gochujang and bring the liquid to a boil to thicken, about three minutes. Remove from the heat.

2. Add the dried anchovies to the sauce and stir to combine.

3. Drizzle with sesame oil and sesame seeds and mix well. Serve warm, or at room temperature.

Yes, when I met Mickey Mouse, I had some unapologetic anchovy breath, and really, that was okay.