Ramen 3.0: Two Former Chemists Are Engineering A Noodle Soup Revolution

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In June, Food Republic is counting the many reasons to love Asian food in America right now. Here's one of them.

The way Jake Freed sees it, there are generally two types of ramen shops in the United States: (1) the traditional mom-and-pop places that strive for Japanese-style authenticity and aesthetics, and (2) the trendy, modern American restaurants that strive for big crowds and big checks. "I don't want to eat ramen when it costs $17 before tax and tip and I have to wait in a long line," says Freed, an Oakland, California-based lawyer and passionate noodle-soup aficionado. "I appreciate ramen as fast comfort food, and that's something that I think has not come of age yet in the ramen market in this country."

Freed and his Japanese wife, Hiroko Nakamura, are currently working to develop a different type of ramen shop in America: one that is reasonably priced and more tightly curated, menu-wise. And, yes, one that is more in line with today's preeminent fast-casual style of service. Sure, they're probably not the only entrepreneurs racing to establish the nation's first Chipotle of Ramen. These days, virtually everyone wants to create the Chipotle of Something. But it's hard to imagine anyone else taking the same approach.

They aren't chefs or restaurateurs or food-service industrialists of any sort. They are both former chemists, and that gives the couple a unique perspective as they work to launch their new restaurant prototype, Shiba Ramen, later this year. "It makes us really empirical about the ingredients we're using, the costs of those ingredients, and what kind of actual impact a particular ingredient has on the product," Freed says.

Talk about empirical: On a recent research mission to Japan, the pair not only tasted a lot of bowls of ramen, they also tested a lot of bowls of ramen, using a hand-held salt-concentration meter to measure the precise sodium levels of each bowl at the various locations they visited. The average salt content came in at around 1.7 percent, but Freed suggests that 1.2 percent is probably better suited to the blander American palate. During recipe testing, the couple has conducted similar experiments on its own soups, employing a digital refractometer to measure the liquid's thickness, he notes. And the duo is determined to serve its ramen bowls at an ideal surface temperature for safe and satisfactory slurping.

In the kitchen or the laboratory, the process is basically the same, according to Freed: "Making sure you have the right reagents," he says, referring to the scientific term for ingredients, "in the right proportions and cooking everything for the right time, and keeping tight process controls so you produce a consistent product."

Nakamura, who has received formal ramen instruction in Japan, will handle the cooking. But don't call her "chef." She has a more industrial-sounding title: vice president of product development and quality control. Freed, meanwhile, is dealing with the business side of the operation.

While the pair is still working out some of the finer points of the business plan, Freed says that streamlining the ordering process is a major focus. Too many existing ramen spots offer "bloated menus" with too many choices — often as many 10 types of ramen and a full slate of sides, he says. Shiba Ramen will launch with just five styles of soup: miso (fermented soybean), tan tan (spicy Sichuan-style sesame and chili), toripaitan (creamy chicken), chintan (clear) and a vegetarian option. And it will offer a few select sides: tebasaki (a regional Japanese style of chicken wings), gyoza (dumplings), onigiri (rice balls) and maybe some pickles. "Here, we're trying to offer something for a wide range of taste preferences without making things complicated," Freed explains. Their aim is cap prices in the $9 to $11 range per bowl, without charging extra for popular toppings like chashu (pork) and egg, the way many places do. Freed suggests they'll be able to keep prices down partly because customers will order at the counter; table service will not be provided. Also: no tipping.

The couple has adopted the ever-popular "fast-casual" descriptor to help emphasize the expediency angle. But in a worldly sense, the idea is more traditional than contemporary, Freed says. In Japan, he points out, many ramen shops operate that way: Payment is quick and easy, and the food arrives fast and gets gobbled up in a hurry. Not a lot of sitting around and socializing like you see at the hipper ramen hubs here in the U.S.

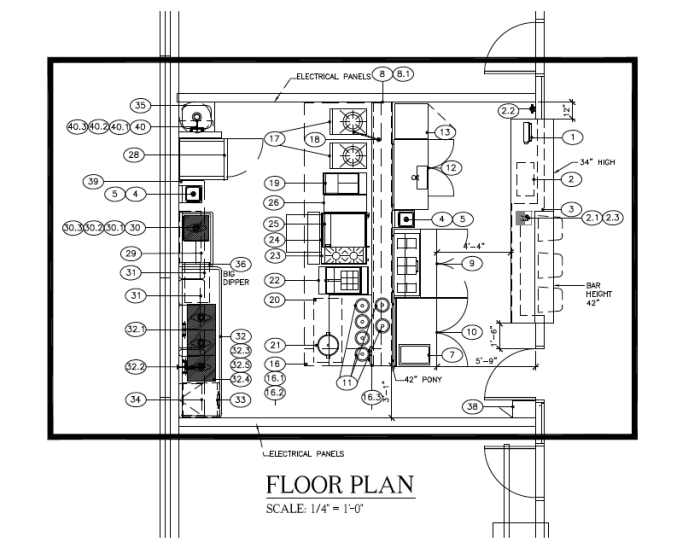

The couple's first location, a 400-square-foot kiosk inside a newly renovated public market in Emeryville, California, is presently under construction and expected to open in September. Seating is available in the market's common area, but there will be a few stools at the ramen counter, as well. While it sounds like a pretty modest operation, the tiny food stall actually represents much bigger aspirations. "Our goal is to expand and have our own brick-and-mortar places," says Freed, though the idea is that future freestanding locations will generally follow the same formula.

Like any good scientist, Freed is keeping a timely record of the couple's progress. You can follow along on his blog, aptly titled Ramen Chemistry.