Why Is Bordeaux Suddenly Stealing From The Loire Valley Playbook?

A well-dressed crowd gathered in the basement of Ginny's Supper Club in Harlem on a recent evening for two main reasons: One was to celebrate the culture of Harlem at one of its liveliest restaurants, owned by celebrity chef Marcus Samuelsson. The other was to experience the cooking of guest chef Sean Brock. As diners spooned Brock's famous Carolina rice porridge into their mouths, they washed it down with a 2013 wine from Graves, Bordeaux's principal white wine appellation, on the Left Bank. The pungent, nutty Sauvignon Blanc and Semillon blend complemented the creamy, mild dish, but it had not been chosen by an in-house sommelier. All of the evening's wines were courtesy of Vins de Bordeaux, a regional marketing organization that seized upon the event as an opportunity to promote a new style of Bordeaux wines — "younger wines made to be enjoyed," according to a rep, with "more fruit, less oak, and organic too."

One of the world's most esteemed wine regions, Bordeaux is best known for its rich, oaky reds, typically left to age in your cellar for years, sometimes decades. Fresh, young, easy-drinking stuff? Not so much. But producers in the region are making a concerted effort to change that. And fast.

It's a stunning shift: If you had told U.S. wine drinkers in the 1990s that Bordeaux would one day need marketing campaigns to emphasize its younger, less oaky wines, they may have guffawed into their Riedel glassware. But this push is, in part, a reaction to the success of wine regions like the Loire Valley, whose wines were virtually not imported into the U.S. until the late '80s — and which is now the region most known for on-trend natural wine.

Socioeconomics is another factor. The region's main importer, Diageo, essentially stopped bringing Bordeaux into the United States not long after the 2008 financial crisis hit Wall Street. If you consider who drank Bordeaux the most, the dramatic pull-back makes sense: It was the preferred wine of financiers and other well-heeled enthusiasts with the resources to support a healthy Bordeaux habit. Wines from Bordeaux — at least in the classic style — have long been on the pricey side. That's partly because they require cellar aging, an expensive proposition in itself. But it's also symptomatic of the "Parkerization" that took hold of the wine market in the 1980s, driving up prices as influential critic Robert Parker's points system created sudden demand for fuller-bodied, mature wines with tannic structure, precisely the kinds of wines that Bordeaux is known for.

When the U.S. financial market crashed, the Bordeaux-drinking class also shrunk. And an importer like Diageo, which had bought Bordeaux futures (meaning, the company purchased the wines before they were ready to be shipped, banking on the vintages and on the estates) and sold them to the New York City market at fairly reasonable prices, suddenly had a lot of product on its hands and a much smaller market to work with. In 2010, the company decided to cut its losses, closing its Bordeaux-focused Chateau & Estates branch because it wasn't profitable enough. After it folded, "restaurant buyers had no access to Bordeaux," recalls Carson Demmond, then a sommelier at the Modern in Manhattan who now works for Duclot, a company that imports exclusively Bordeaux to New York City.

American wine drinkers, meanwhile, turned their attention elsewhere. "Basically, the U.S. became more interested in wines of elegance just as efforts to get higher Parker points led to increasingly inelegant wines," says Jeff Patten, the owner of Brooklyn's Uva Wines since 2005. [Disclosure: I once worked for Patten at Uva.] "The Bordelais were able to sell their wines into the Asian market at ever-increasing prices. So the U.S. just stopped buying and they switched to Burgundy and now Piedmont."

If winemakers in Bordeaux hope to regain a foothold in the U.S. market, then they'll have to market to a different type of American drinker. Margaux and Haut-Médoc don't carry the same cachet with today's generation of wine directors; instead, they talk up muscadet, Brouilly, and carbonic maceration. Hence the marketing campaign to reach Gen Xers and millennials who now treat wine the way the foodie movement is treating ingredients: with concern for additives and an interest in stories about the artisans who make the wine. The natural-wine movement is going strong Stateside, and it has led drinkers who want to enjoy life, but don't have deep pockets or wine cellars, to regions that produce affordable quaffs. Loire in, Bordeaux out.

Converting this coveted new audience back into Bordeaux drinkers requires a dramatic shift in approach for the region's marketers, who historically haven't needed much self-promotion for their higher-end wares. But there is far greater competition among lower-priced wines. And even if Bordeaux is producing excellent stuff at reasonable rates, it's a lot harder to get attention.

"The way the market is today, there's so much competition at that price point," says Mike Madrigal, head sommelier at Bar Boulud and Boulud Sud in New York City. Madrigal hosts events on behalf of Planet Bordeaux, a company that promotes Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur AOC wines, the humbler classifications of the region. He says that the "growers of Bordeaux want to yell it from the mountaintops: 'We're here, we have amazing value, wines of typicity,'" referring to wines that reflect the regional terroir and grape varieties. "And they're $15.99 or $19.99 on the shelf," he goes on. "They're like, 'We need to get louder, stop being so humble.'"

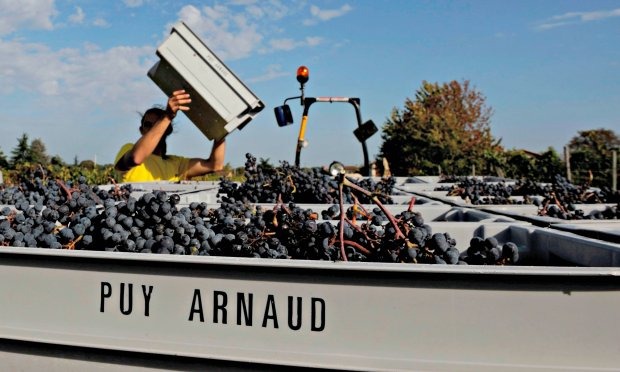

One winemaker who perhaps best embodies this bold new era in Bordeaux is Thierry Valette at Clos Puy Arnaud in Castillon, located on the southern end of the Cotes de Bordeaux and Right Bank of the Gironde. Valette, who had a career in modern and jazz dance before he purchased his 15-hectare estate in 2000 at age 47, discovered biodynamics through a consultant named Anne Calderoni and now turns out organic, low-sulfur wines made without artificial yeasts. His wines are alive and fresh in the way natural-wine drinkers prefer, but they also display typicity of the grapes and region.

Valette's Cuvée Bistrot, for instance, is a light and fruity blend of Merlot and Cabernet Franc. This is what the French call glou-glou, meaning it goes down easy. It's made using partial carbonic maceration, a technique developed in Beaujolais in which grapes burst in a tank, instead of being crushed, for a fresher taste. And it's available here in the U.S. through the importer Duclot; the 2012 vintage retails for around $26.

Valette also exports a wine, called simply Clos Puy Arnaud, that sees one year in oak, with roughly the same blend of grapes. It is more classic but also approachable and light. Look for the 2011 vintage, priced at around $44.

The first-growth chateaux may never go completely out of fashion. But in today's radically transformed global economy, this genre of less oaky, natural-leaning wines may be crucial to Bordeaux's survival.

Read more wine stories on Food Republic: