10 Questions And Answers With The Author Of 'Bread Revolution'

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Peter Reinhart explores new developments in the world of bread in his second work.

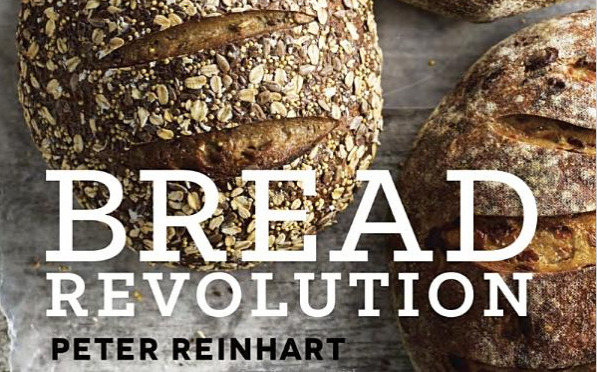

Peter Reinhart is the author of Bread Revolution: World Class Baking with Sprouted and Whole Wheat Grains, Heirloom Flours, And Fresh Techniques

What is this book about?

A few years ago, I realized there was a growing movement for bread using flour made from sprouted wheat and other sprouted grains. One of the few millers in the country making this kind of flour asked me to test his sprouted whole wheat flour. I was extremely impressed by the flavor. It was better than any 100% whole wheat bread I'd ever made, even those using advanced bakers' tricks such as preferments and slow cold fermentation. It was smoother (no rough, scratchy taste in the back of the throat), sweeter and softer than the usual whole wheat breads, yet I made it with only the sprouted flour, salt, yeast and water. I started playing around with it, along with other types of sprouted flours, such as gluten-free versions and even sprouted bean flours, and felt that this represented a new frontier for bread bakers.

In my explorations, I also learned about other new developments in the world of bread, such as using sprouted grain pulp, regional-specific heirloom flours and even flour made from dried coffee cherries, grape skins and grape seeds. Just when I thought the baking community had explored pretty much everything there was to know about bread, I saw that we were actually in the early stages of yet another revolutionary phase. This book explores some of these developments through formulas and profiles of some of its pioneers.

What is the difference between sprouted flour and sprouted pulp?

For the past 50 years, there has been a popular alternative bread on the market made with sprouted grain "pulp" or "mash." The two most well known brands are Ezekiel Bread and Alvarado Street Bakery. The grains are soaked, germinated and then slightly sprouted. It is then ground into a wet pulp in a machine similar to a meat grinder. Other ingredients are added — yeast, salt, sweetener and pure wheat gluten — and a very tasty bread emerges that is, technically, made without any "flour." The sprouted pulp requires pure wheat gluten (also called Vital Wheat Gluten) to replace the gluten that is destroyed during germination and grinding. It was assumed that any bread made with sprouted grain would require this additional gluten in order to be light and airy.

When a few millers decided to try drying the sprouts without grinding them, and then milling the dried sprouted grain, it made a very fine flour that tasted different from non-sprouted grain. To everyone's surprise, the gluten wasn't destroyed in the sprouted flour and, when reconstituted as a dough, it performed like regular bread but tasted better and contained the health benefits brought about by sprouting. Now we have two ways of using sprouted grain in bread — dry flour and wet pulp — both of which provide the benefit of better nutrition and better flavor.

Can you explain more about the nutrition?

It has long been known that when grains, seeds and beans are sprouted, their nutritional value increases dramatically. Not only does the mineral and vitamin content increase but the starches are also affected by enzyme activity, releasing their natural sugars, and digestibility improves while lowering the glycemic load.

Now, just how much of the nutritional potential that survives the baking process is still being studied, but we're seeing a lot of anecdotal evidence that shows positive digestive benefits. Of course, the fact that the sprouts are also whole grains is already a positive from a prebiotic sense because of the increased fiber. I expect to see a lot of encouraging new studies emerge in the next few years.

What about the flavor? Why does it taste better?

A seed or grain kernel is a highly concentrated package of nutrition designed to nourish new growth. Enzymes, which are small proteins that act as keys (or scissors) to break up carbohydrates or long protein chains, begin to activate when the seed is hydrated and germinated. There are a lot of implications of this activity but one is that nutrients are freed up, as are various sugars that can serve as food for both yeast and lactic bacteria (the good kind), resulting in better flavor and a richer color (that is, better eye appeal, not to be taken lightly when it comes to how we enjoy our food).

Do you address the gluten-free movement in Bread Revolution?

I did not want to repeat what I wrote in my previous book, The Joy of Gluten-Free, Sugar-Free Baking, but Bread Revolution does offer a few new gluten-free recipes that feature sprouted gluten-free flours and nut flours. New information is coming out every day to clarify some of the misconceptions and false assumptions surrounding gluten and other allergens, so this category will continue to be an important part of the bread revolution.

Any new discoveries about sourdough bread?

I keep learning more and more about the microbiology underlying sourdough bread, so I included my latest findings in this book. As the research shows, there is something very different about bread made with natural wild yeast starters (aka natural leaven) as opposed to commercial yeast. I think that even more information is still to come that will show the health and digestibility benefits of naturally leavened bread, both whole grain and white flour versions.

Besides sprouted grains, what other "new frontiers" are happening in the bread world?

The book takes a peek at flours made from grape skins and grape seeds, as well as varietal grape seed oils. In addition, I profile a new grain product called ProBiotein that serves not only as a healthy prebiotic fiber supplement but also acts like a sourdough starter when added to bread dough. Flour made from the dried outer husks (called the "cherries") of coffee beans also shows great promise in both culinary application and in the natural healthcare market. In the last chapter, I explore the next new frontier by profiling a baker who has come up with a unique method of creating one-time-use starters.

How big do you think these new frontiers will get?

Gluten-free went from a fringe movement to a multi-billion dollar industry, but not every new bread frontier tips over into something major. Sometimes a small wave can lead to a larger one later on, though; for example, I'm not convinced that grape skin flour will make a huge impact in bread baking, per se, but it clearly has many other nutritional and flavor implications that could inform health care products. I do believe sprouted grain flour is going to be a game-changer, which is why it's the focus of this book.

You also wrote about an unusual sourdough bread method. Can you give us a little preview?

A baker friend taught me a new method that involves making a starter using hand-squeezed (through a cheesecloth) apple, pear or peach juice added to flour. He influences the flavor by resting various ingredients on top of the starter bowl to draw out particular microorganisms. He uses Parmesan cheese, coffee beans and different types of fruit to create subtle flavors. He uses the starter only once, instead of feeding it to keep it going, because he worries that the starter will change its flavor profile if it is refreshed, which will cause him to lose control of the taste. A very interesting chapter.

What's next? Are there bread frontiers not yet seen? Any predictions?

Considering that humans have been making bread for at least 6,000 years, it's amazing that we're still learning new ways to make it even better. Enzymes, bacteria, new strains of yeast, selective and directed seed breeding, small regional mills using locally-grown flour — the growth never seems to end. I think we're actually headed into a golden era for bread. I'm thrilled to see what's next!