How To Read The Earliest Food Writers

Most of us dine on the bon mots of Tony Bourdain ("Don't touch my dick, don't touch my knife") and Mark Bittman ("You eat more plants, you eat less other stuff, you live longer") like they are the yin and yang, the ne plus ultra, of everything we ever have to read about the meaning of food. And, no doubt, those boys are clever and funny about what we eat, like nobody's business.

But what a shame that we neglect to appreciate their predecessors — the culinary sages who have been lost to history. What, you say you can quote Julia Child like scripture? Let's skip that grand dame too, and go way back to honor the food writing stars of yore, foodies before they were called foodies.

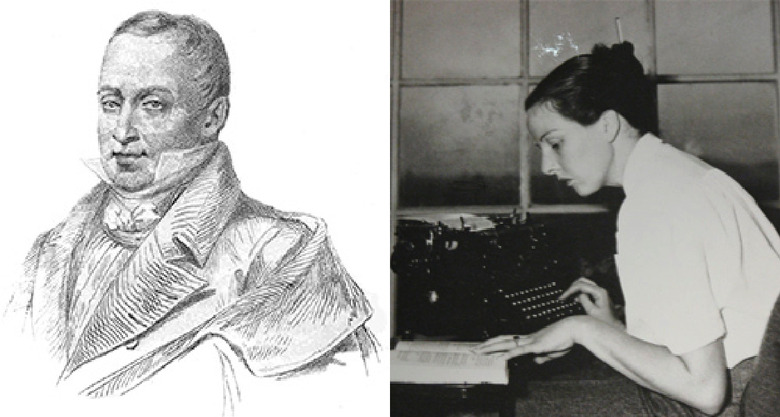

First on our list is the early 19th century's Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, a Parisian politician who, in his later years, published the seminal work, Physiologie du Goût (The Physiology of Taste). Brillat-Savarin treated eating like a science, as well as a source of philosophical contemplation, dishing out ruminations ("Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.") and side-splitters ("A dessert without cheese is like a beautiful woman with only one eye").

Brillat-Savarin and his contemporary, Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière, another Parisian, established what we know today as food writing. Grimod, a theater critic who also threw great dinner parties, went on to become a food critic and published the first modern restaurant guide. Grimod knew how to chow down, and lifted the bar on what he called, the "art of dining."

Eliza Acton may not have had a French way with words, but the English poet knew her way around a locution or two; she is credited with writing one of England's first cookbooks, in 1845. Acton, who cooked up the idea of listing ingredients along with suggested times, once wrote that "a gentlewoman should always, for her own sake, be able to carve well and easily the dishes that are place before her that she may be competent to do the honours of a table at any time with propriety and self-possession." The prose doesn't exactly leap off the page.

For a more inspiring wordsmith, we need to head to the mid 20th century to M.F.K. Fisher, who by all accounts was the Joan Didion of food writing. Poet W.H. Auden wrote a forward for one of Fisher's many book saying, "I do not know of anyone in the United States who writes better prose." (Fisher didn't return the praise, indicating in her letters that she was unimpressed with Auden's forward.)

Beginning in the 1930s, Fisher wrote more than two dozen books, with an unparalleled sauce and style — dispatching odes to oysters and advice on how to cook a wolf. Living in California and Europe, she married three times and cooked constantly, spending "hours in my kitchen cooking for people, trying to blast their safe, tidy little lives with a tureen of hot borscht and some garlic-toast and salad," she once wrote.

Her writing recalls Hemingway ("We sink too easily into stupid and overfed sensuality, our bodies thickening even more quickly than our minds."), but it's best not to compare. She stands alone. Just read: "Like most humans, I am hungry...our three basic needs, for food and security and love, are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others. So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it." Hmm, food for thought, indeed.

Fisher, who died in 1992, inspired Craig Claiborne, a World War II veteran from Mississippi, to enter the world of food publishing in the 1950s. After becoming the food editor at the New York Times, Claiborne introduced the paper's readers to the expanding world of international cuisine. He's also credited for not only coming up with the four-star system that's still in use today, but also launching Julia Child's career with her first book review. A very good biography was just released.

But Claiborne was a renowned writer in his own right; "Give me a platter of choice finnan haddie," he wrote in his column in the early 70s about smoked fish. "Freshly cooked in its bath of water and milk, add melted butter, a slice or two of hot toast, a pot of steaming Darjeeling tea, and you may tell the butler to dispense with the caviar, truffles and nightingales' tongues."

Ok, so maybe he, like these other legends, sometimes ate and wrote in ways that we can't entirely appreciate today. But without them helping to push the food culture ever forward, we might be eating corn out of a can.

That bad boy Bourdain, once said, "when you write about food it's like writing pornography. I mean, how many adjectives can you use to describe a salad?"

Even if he was being cheeky, he couldn't be more wrong. Tony, just dine on these profound words from Grimod: "Life is so brief that we should not glance either too far backwards or forwards...therefore study how to fix our happiness in our glass and in our plate."