The Importance Of Menu Design

With our ever-expanding obsession with food culture, we've gorged on essential ingredients, budding brew masters, exotic eateries, and — ok, enough with the alliteration already! — knife wielding techniques. And while the dining experience has been sliced and diced in never-ending ways, there's one neglected element that's been right in front of us all this time: the menu.

"There are 16 million restaurants in the world," says Aaron Allen, a successful Orlando, Florida restaurant consultant and menu design engineer. "The one thing they all share is a menu."

OK, so maybe the total number of restaurants is a hard number to come by — it may be closer to 8 million, for all we know — and, the truth is, some of those eating establishments might serve just one dish, beef tongue on cassava cake, perhaps, on a dirt patty. But we agree with Allen's point: menus are important.

"You kidding? It's everything," says Frank Castronovo, of the Frankies Spuntino empire in New York City. Castronovo says he and his partner, Frank Falcinelli, put a whole lot of thought into their menus. "It's what describes your product," he says.

It would be naïve to think that the menus we read when we sit down at a restaurant are just innocent, off-the-cuff descriptions of food options. That's where a guy like Allen comes in; he's hired to apply a coterie of menu design techniques that are time-and-focus-group tested to sell. It's a booming field in restaurant consultancy. "What we emphasize is that the menu is the spokesperson," Allen says. "It communicates the brand position, the brand personality and the brand story."

"It can be a memento of an experience. I like how the menu can contribute in a subconscious way to the level of your experience."—Wylie Dufresne

And, to get a little touchy-feely, menus mean something. They are associated with our favorite meals, our favorite moments. It's no wonder, then, that Wylie Dufresne has his own "massive" collection of stolen menus from different restaurants. Dufresne, who says he doesn't condone such thefts, admits to having done so, because "I respect the work that goes into the creation of one," he says. "And it can be a memento of an experience. I like how the menu can contribute in a subconscious way to the level of your experience."

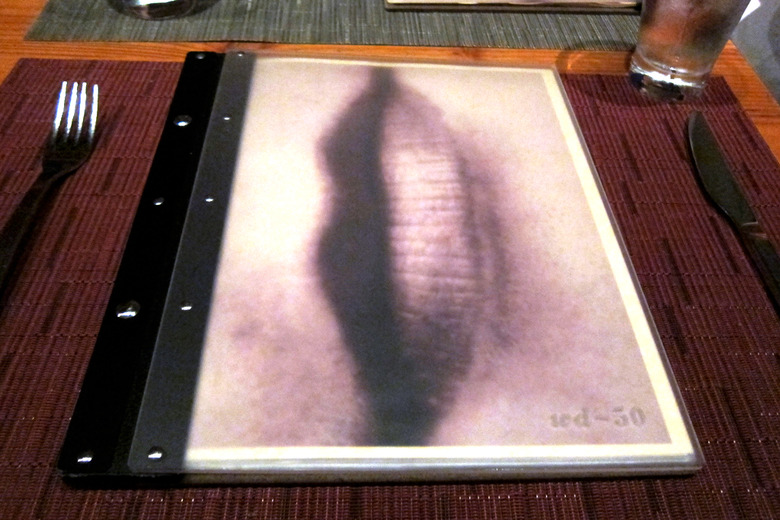

We at Food Republic decided we'd like to break down restaurant menus in a multi—part series; first, early next week, we'll talk about the menu at Dufresne's WD-50 restaurant with the chef/owner himself, and then trace some of the ins and outs of menu engineering. We'll also answer that beguiling question: where's the most valuable spot of real estate on a menu?

Allen, who boasts work with half of the Top 400 largest restaurant chains in America and a global client roster that generates more than $100 billion, could answer that last question in a heartbeat. He's on a slightly different wavelength than Travis Kauffman, who earned his MFA in Computer Art at the School for Visual Arts, and who helps Castronovo design his menus. Brooklyn-based Kaufman works closely with the Franks, who often revise their menus. "But we're not into any tricks or gimmicks," reports Castronovo.

Allen has more of a, shall we say, commercial approach, and he speaks authoritatively about how the layout of a menu, and the placement of a particular dish in a particular spot, can immediately generate sales. Allen also has at least 30 "go-to menu merchandizing techniques," that include use of color, boxes and different means of highlighting, that he can apply to a menu. Of those 30-plus, he doesn't recommend more than two on a page, and almost always under five on an entire menu.

That gives us a headache to think about, but in a world overrun with market research, it shouldn't surprise us that menus are being produced by formula. After all, the Culinary Arts Institute has its own Department of Menu Research & Development. Still, not all restaurants create menus like paint-by-numbers.

"I feel I work in a more intuitive way," says Kauffman, who admits the Franks still bring a fair amount of menu science know-how to the table. "And maybe I use more of my fine art career to inform my work rather than some marketing techniques." Proving his point, Kauffman says that the Frankies menus buck the trend of very clean, Spartan spaces, and instead "fill up the blank space. We go corner to corner," he says of an aesthetic born from a dedication to a vibe inspired by a turn-of-the century eatery that Italian immigrant might appreciate. "We pack items and text everywhere."

By the way, Kauffman didn't correctly answer the question about the most valuable part of real estate on the menu, as professed by Aaron and other design engineers. But he has nothing to worry about. As he says, nine years of restaurant success with the Franks is enough to convince him that their slightly off-the-grid approach works.