How Letter Grading Is Blowing Up My World

The Bloomberg administration ostensibly introduced the letter grading system for restaurants in order to inform the public of the apparent cleanliness or sanitary quality of the city's 24,000-plus restaurants, delis, etc. (For those of you unfamiliar with NYC's system, here's a primer.) The administration has worked hard to keep the city solvent over these challenging years of economic crisis, to find revenue wherever revenue can be found. The timing and implementation of this system, however, seems too convenient a method for squeezing more blood from an undercapitalized, albeit large, segment of the city's businesses. It's a disingenuous manner of standing on a soapbox and preaching improvement while increasing department of health revenue over 140%.

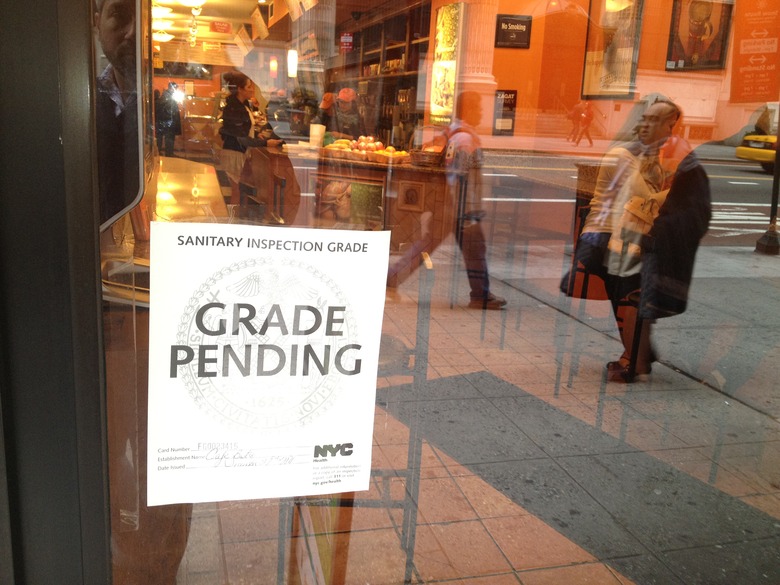

Let's first look at the way in which the system flaunts itself in the windows of the city streets: prominently displayed iconography, the all-too-familiar letter grade system. Like any system attempting to address a large sampling of seemingly similar but truly distinct people and businesses, there are bound to be imperfections. And, like the star system to which Pete Wells recently stated that The New York Times will continue to adhere, the letter grade is an ambiguous catch-all into which these businesses must be categorized. The difference between a reviewer anointing a restaurant with stars and a city department slapping a business with a letter grade is that one is subjective while the other, by its very nature, cannot be. And, a cause for much of the flare-up is that the practice, the on-the-ground inspections—the reality from which heads of departments, cities and administrations are detached—remains completely arbitrary. Inspectors work on interpretation born out of ignorance, not clear, well-researched and regularly updated guidelines, a scary subjectivity that, to the benefit of the department itself, has resulted in a huge uptick in fines.

At what point will the city stop plucking the low hanging fruit and turn its sights on the myriad more sophisticated businesses within its confines that generate more revenue and much more profit? The cost of acquiring the permits required to run a business that serves food and alcohol, has outdoor seating and, oh my, a section in which one can legally dance, is already wildly out of touch with this business where making 10% to the bottom line is considered a success.

To then swarm these businesses with health inspectors mandated to find the aberration, to scrutinize to a level out of touch with the nature of food production, appears to be aggressive and shortsighted.

The answer is education, education, education. Exposing people to information and guiding them through the process of analyzing and critiquing the information: this is education. This is where we fail, in so many areas, in the relationship between restaurants and the city's Department of Health.

Education, properly provided, results in nurturing relationships rather than antagonistic relationships. The overwhelming sense is that the poor education of health department inspectors creates insecurity, particularly when presented with an articulate chef or restaurant owner operating a modern and creative kitchen. And we all know that insecurity manifests itself as animosity which then closes one's mind to logic—an environment as toxic, if not even more so, than the anaerobic conditions that can foster botulism.

Chefs and restaurateurs are much more sophisticated than they were even five years ago. More and more highly educated—and I'm talking about post-baccalaureate degrees—folks have taken to cooking, food production and mixology. Given the right platform, New York can still be the best place to practice and advance this art.

This can happen if, for a moment, the city allows all grades to remain pending, pending an investment of this windfall of dough from restaurants that have paid fines to the city into the education of its health inspectors. This education should be conducted with representatives from the city's restaurant community teaching several seminars.

We should look to other cities, other cultures and to scientific fact to really understand the nature of food production and work to dispel myths about bacteria, low temperature cooking and storage. Each party in the equation has a vested interest in the success and survival of this colorful and entertaining segment of the city's business community. Let's not derail ourselves to an abysmal fate where small, personality-driven businesses feel hunted by the faceless machine of the city.