The Art Of Sanford Biggers

At 40, Sanford Biggers has already achieved what many artists would kill for. Whitney Biennial? Check. Tate Modern in London? Check. Exhibitions all over the world, from Japan to Texas to Berlin? Check, check, check. So what's next for this bright young visual artist, whose work ranges from video to sculpture to multi-media mishmashes? An exhibition of new works, Cosmic Voodoo Circus, at the Sculpture Center in Queens, opening September 11, and a survey of installation art at the Brooklyn Museum this fall, opening September 21, plus lots of other illuminating stuff.

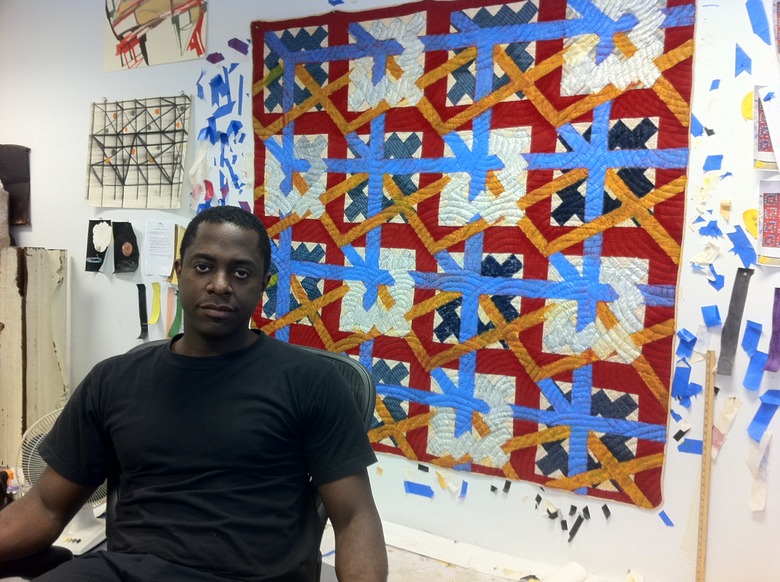

We popped in on Biggers in his Harlem studio just a few weeks before he took part in the other night's Food Republic panel and cocktail party. And though it was meant to be a casual conversation, the interview ended up ranging from a quilt project he's making that references the Underground Railroad to Bob Marley, hip-hop, racial identity, Indonesian gamelan orchestras, cooking, growing up in LA, and much more. Deep, but then that's not surprising coming from a guy who teaches at Columbia University when he's not jet-setting to art shows and fairs.

*Warning, this is a long one, but Biggers is an amazing guy; plus, if you get to the end, you can see a full video clip of one of his art short films, which incorporates music that he makes himself.

Let's start talking about your art first. You have a lot coming up this year. What are you working on?

Right now, I'm working on several different pieces for these shows coming up in Brooklyn and in Queens. I'm doing more quilts here. These quilts relate to the history of the Underground Railroad and how quilts were used as markers. As escaping slaves would travel up north and would go to safe houses, these safe houses would sometimes fold or use a certain pattern of quilt to announce whether they were under surveillance, or if everything was in the clear and they could stay there that night. So these were like little subtle road marks for escaping slaves.

What would happen if the quilt denoted that it wasn't safe?

They'd keep going. No sleep, and keep going to the next one. Obviously, it was a railroad and a lot of different stops in a whole intricate network and the abolitionists, slaves, and the conductors of the Underground Railroad — which were mostly freed slaves, but also sometimes abolitionists — everybody was sort of in cahoots. They devised these systems of demarcation like quilts, or lawn jockeys; sometimes they'd tie bandanas to the lawn jockeys and the police would just think that these were decorations and not really know that there was this language attached to it.

How do you incorporate such references? I imagine there's an inspiration point to thinking about using these type of signifiers from the Underground Railroad and deciding to incorporate it into your art.

Well, I guess I consider history to be a material. They say history is written by the winners, they also say history is "His-story." There are all these views of history and not all of that historical stuff is fact; a lot of it is conjecture. I think there's ways to re-appropriate used history as literally a medium, changing its meaning, changing its context, which can allow for different interpretations. Psychologically I think that came to be important, especially during the time when there is the potential to re-examine African Americans in America, via Barack Obama or just some of the things that are happening. I mean, he's a great example but he's not the best example, for obvious reasons.

But I also see this project extending far beyond just African American history. I mean American history encapsulates so many different regions, so many different ethnicities. It's really about finding a way to understand things that have already happened in order to change and reinterpret the ways things may go and move forward.

What about some of the historical figures? I mean Harriet Tubman is an amazing jump-off as far as a historical figure but one of the first things that caught my eye walking into your studio was a picture of Bob Marley. What about a figure makes it important enough to consider them a jumping-off point in your art?

That's a really good question. And for the most part, I try to use a lot of figures that aren't really recognizable, and Harriet Tubman is recognizable but Bob Marley is far more recognizable. However, it's interesting you bring him up because I learned a lot of history, as many people do, from listening to Bob Marley, or reggae specifically, because that's exactly what it did; it became an educational device as it would go through the history of Africa, Haile Selassie and Rastafarianism and Marcus Garvey. In the same way that reggae was used to sort of educate people, I'd like to think that my work can do that — as well as entertain, seduce, challenge, and explore. It's not so much that I want my work to answer questions, but I want it to provoke better questions from the viewer.

You grew up in LA. At the time you were growing up, I'm sure you were exposed to the East Coast/West Coast hip-hop controversy. Did it affect you in any way, the dichotomy?

Not, not at all. I honestly thought it was a joke the whole time they were doing it. And when it started it really felt like it was a tongue-in-cheek way to "let's just get some hype going," like in the old-school battle sense. But then it just got taken way too literally, obviously.

When I grew up, the first stream of hip-hop we got came from the East Coast, so that was basically the Bible and the birthplace and we acknowledged that.... Then we started to get West Coast Rap, you know with Dr. Dre and the Wreckin' Cru, early early stuff. Then I went to Atlanta for school right when the Southern stuff started to come up, like Geto Boys and 2 Live Crew. And by the time I was leaving there, OutKast came out with their first album and the nation didn't even know who they were yet.... I would never claim, you know, East, West, or Southern. At the end of the day it was just music. But I think it was good for hype and then horrible for the consequences that came from it.

What about growing up in LA? I was just in LA talking to a chef about trying to teach people to eat better; that's been in the news recently with the new MyPlate announcement. We were talking about the differences in the areas around there in terms of the Black and Latin communities and trying to teach them to eat better, and how it's not as easy as Washington is making it out to be—

No way, people in the hood are not going to go to Fairway and Whole Foods. And even if they did, they wouldn't be able to afford it because we can barely even afford it. That's crazy. But oddly enough, my parents, older generations, sort of got it. I mean they were eating some bad stuff, don't get me wrong, but they would also throw some vegetables in there. It's as basic as that when you're talking about Inner City diets and nutrition. I mean I have some friends who won't even touch vegetables and can eat meat all day. It's just ridiculous.

But what's your personal relationship with it? Were you very affected by growing up in that environment?

I mean there were some Twinkies and that kind of stuff, but somehow it was all well moderated. And my mom cooked everyday, so there were always vegetables and salads and leafy greens and fruits and healthy things. Fast food was a treat, it was a special thing, but it wasn't an everyday thing. But that was me and I was fortunate to have that. I grew up middle class and went to private high schools. But right in my neighborhood there were people just living off of fast food and Twinkies and Ho-ho's and candy and McDonald's. I think a lot of it is access, and education is a huge part, but access is an even bigger part. I mean people eating McDonald's every day don't necessarily want to eat McDonald's every day, but you can't argue with a 99-cent menu. And it's on every corner.

What about living and working in Harlem? It's not exactly easy to find healthy food up here. What do you do as someone that's a little more enlightened than most people around you?

It's been hard. I've been living in Harlem since 2000. Until I dare say two years ago the only real healthy food around here was Strictly Roots, the vegetarian spot. Other than that, it was fried chicken and Jamaican food. That's it!

Do you cook yourself?

Yes I do.

What do you like to cook?

Particularly fish. I've been getting into cooking lamb lately. I try not to eat too much red meat, but every now and then I have to do a steak. Vegetarian lasagnas, omelets, frittatas, that kind of thing.

How did you learn?

Growing up watching my mom, being in the kitchen. I think cooking is very similar to music or art, as early exposure, you just start to become accustomed to certain things. There have been long periods of times where I haven't cooked and I notice it's difficult to get back into it because you lose your "chops," but if you're cooking regularly you start to become more fluent and experimental, you get away with more things and know how to make things just sort of work.

What about the setting for you? If you're going to take the time to go out to the store and come back, do you put on music or get sort of involved in the whole process?

Sure, sure. I usually make myself a cocktail, pour a glass of wine. Then do all the prep work and have some music on, or sometimes NPR or a movie that I don't have to pay too much attention to. And if I'm feeling really generous and I have people over, of course conversation and I'm involving them in the prep.

When you're in the process of cooking, do you see some of the similarities between making a dish and making a piece of art?

Absolutely! Because as an artist, and I tell this to my students and practice this in the studio, you sometimes make a "mistake" in art, and I look at that as an excellent opportunity. It breaks you from what you thought you were going to do and challenges you to find your way out of it. They use the expression a lot "painting yourself into a corner," and sometimes you have to paint yourself back out of the corner. And with cooking, it's the same thing. You put a little too much of this or you're missing an ingredient that is asked for in the recipe and then you have to improvise, and that's sometimes when the best things happen. Of course, there are some failures, but you learn from those failures. I've watched several people cook and there are tricks, there are ways they can blend, just like mixing paint; there are ways you can substitute one thing for another thing. It's amazing.

Shuffle (The Carnival Within), 2009, Two channel HD color video installation with sound component, 4:47 min., Courtesy the Artist and Michael Klein Arts, New York, NY

Sanford Biggers video from Food Republic on Vimeo.