Here's everything you need to know about the best way to keep your kitchen faucet head clean, why it's important, and what the cleaning process entails.

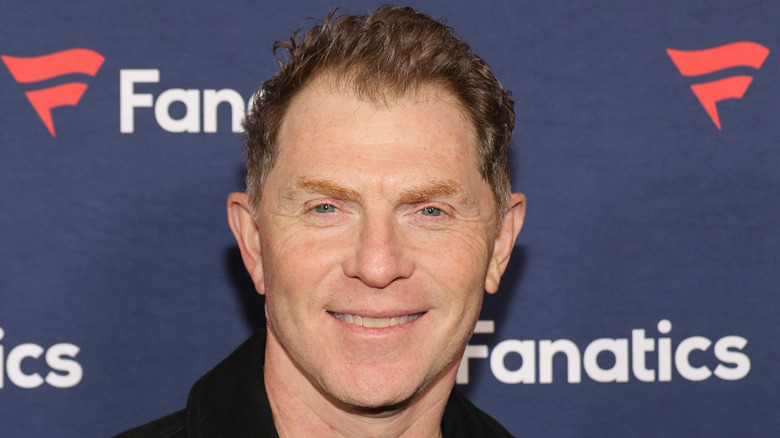

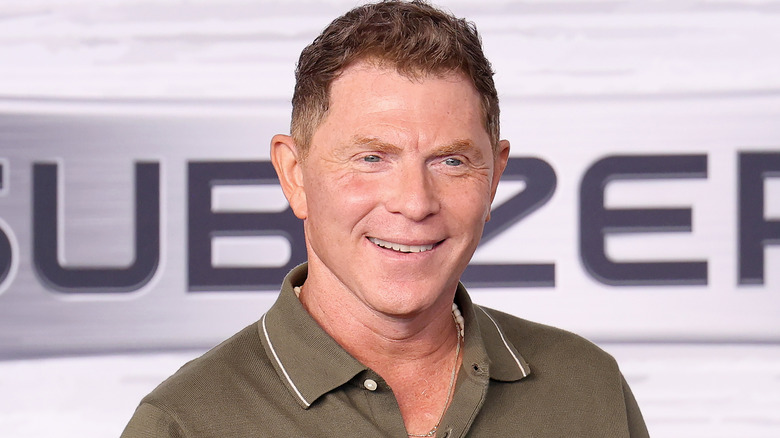

Don't Worry, Bobby Flay's Dessert Pizza Still Has Cheese

When you picture dessert pizza, you probably don't picture it covered in mozzarella, but Chef Bobby Flay has a recipe incorporating another delicious cheese.