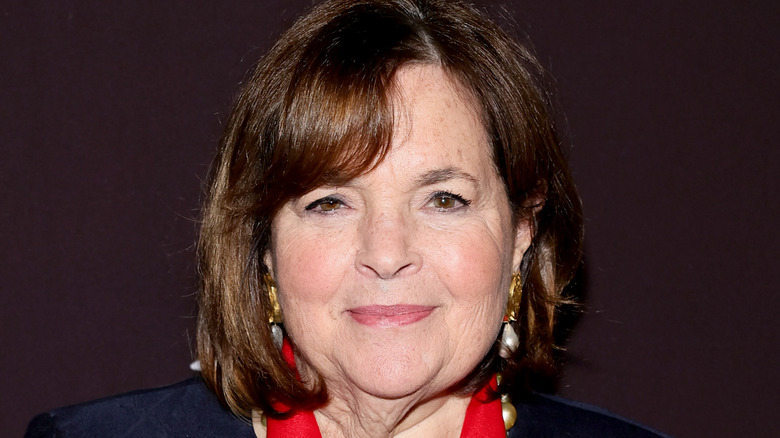

Ina Garten, queen of the Hamptons and our hearts, has the best suggestion for how to determine if a bar is worth its salt or not, and it involves a classic.

A Cooling Rack Is Key To Whipping Up Mashed Potatoes In A Flash

Mashed potatoes are a joy to eat, but can be a pain to make - unless you try this great tip to use a cooling rack on the spuds to speed up the process.