A Brief History Of Cookbooks

"Put soup meat and bones in cold water, let come slowly to the boiling point. There should be about 3 parts of lean meat to 1 part of bone, and 1 quart water to 1 pound meat. Cover tightly, let simmer steadily for 3-4 hours, according to the cut and size of meat. Add vegetables and cook slowly until well flavored. Onions, celery, celery root, parsley root and carrots are used to flavor soups." — The Settlement Cook Book: The Way to a Man's Heart, 1947, Chapter 9, Soups, Published by the Settlement Cook Book, Co. Milwaukee, WI

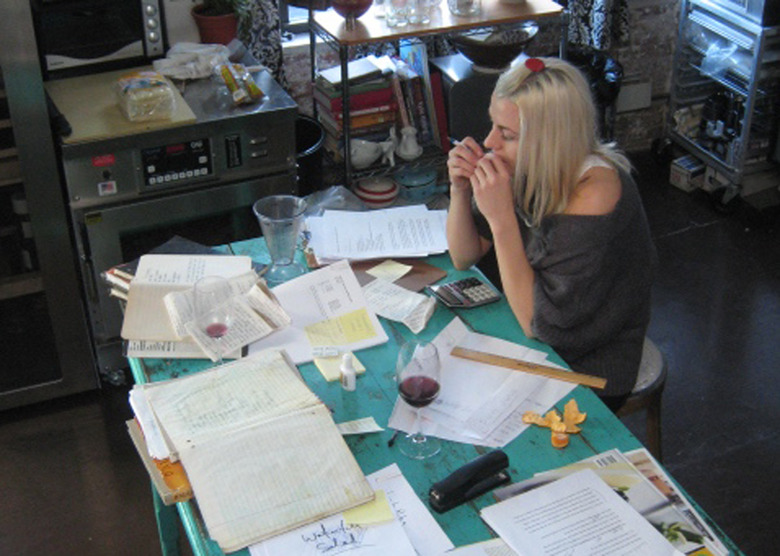

Procrastinating packing and facing the dull reality of an imminent move, we've been taking time to sort through some of our old stuff. Leafing through cookbooks, new and old, has been the greatest pleasure of the calm before our self-imposed storm. We find long-forgotten notes stuffed neatly into the books, holding a page for a recipe that we may or man not cook. This opens up the past for a moment, and reflects the simple passion we have for cooking.

As we've lingered over these books, we've noticed the evolution of the recipe format and the amount of detail added to it over decades and even centuries. The excerpt above is actually a complete recipe from the middle of the country written in the mid-20th century. This is a simple, succinct recipe for a stock and/or soup base that assumes the reader is neither a young child nor a complete incompetent, but that he or she knows the basics. The reader is required to intuit quantities, pot choice, heating method and product selection, and therefore will have most likely cooked a meal or two in her life prior to picking up this book. The Settlement Cook Book was written for a specific demographic, as most were, and, in fact, recipes were tested by a very specific demographic, as listed on the title page:

Tested Recipes from

The Milwaukee Public School Kitchen

Girls Trades and Technical High School,

Authoritative Dietitians

and Experienced Housewives

It's a for us, by us design. That is, written by housewives and cooks for housewives and cooks. The format of the recipes is simple while the content is not: Halibut and Shrimp à la Newburg; Wine Sauces; Brandy Sauces and Chestnut Vegetable (yes, that's the actual title of the recipe). These are some of the recipe headings in this overstuffed tome. One has to have a base level of experience in cooking, home or professional, in order to take full advantage of this book. It was written during a time when most folks cooked their dinners at home and, more often than not, the dinners were cooked by the women of the house.

As we moved into the 1960s through to the present, we noticed that recipe formats have become more detailed, written in a manner that implies the philosophy that no instruction is too obvious, however wordy a simple recipe may become. The fantastic River Cottage MEAT Book, published in 2004, is the perfect example. Hugh Fearnly-Whittingstall's "Making Stock" section is spread across nine pages that are packed with fastidious detail concerning every possible component of a stock. It is even further broken down for making stock with specific types of bones (e.g., game, lamb, beef, veal, pork). One has to read the entire nine pages to grasp how to make a simple stock. This is a lengthy lesson, and perhaps rightly so, as many dishes require a stock as the base ingredient and it's better to have a well-made stock than a poorly made stock. The rub: it would seem as if this book is written for someone who doesn't know a great deal about cooking, but it is verbose and so jam-packed with details that the simple procedure for making a stock needs to be distilled from the pages by a trained eye, or palate, and therefore seems somewhat inaccessible to the novice or uninitiated.

The MEAT Book is not alone in falling into the overly descriptive category. In writing Zakary's book (due out in April 2012 from Ecco), we found ourselves looking at each other, eyes raised, and asking "seriously?" in response to many of the details we were asked to supply. The editing process included questions such as: "At what heat? Medium high? Medium low? How long does it take to brown onions and medium high heat? Should they add salt at the beginning or end?" The prevailing thought would appear to be, make the book accessible to all and/or play to the lowest common denominator. Someone who already knows how to cook will quickly sift through the details already known, but there is a huge market out there of folks who have little to no relationship with food except in restaurants or takeout bags, but who, from time to time, will pull out a book and try to cooking from recipe. The detail is for the infrequent user.

That's cool. We're happy that folks who don't, or rarely, cook actually like to buy cookbooks. The nagging thought, though, is that there are a bunch of folks out there who do cook often but don't have the ability to cook by intuition. Is that so? We don't know.

What we do know is that there is a place for both, and the cook in us has a certain affinity for that which is left unexplained, the note that was not played. The touchstone, for us and many others, for this type of recipe writing is Pellegrino Artusi, who begins his chapter of The Art of Eating Well (note, NOT cooking) on Brodi e Sughi in the following manner, "As everyone knows, to obtain a good broth, you begin by placing the meat in cold water and keep the pot at the barest simmer, so it never boils over." In the editor's note, following this description of broths, a clarification: "Artusi assumes you know the basic procedure." In the 19th and early 20th centuries this may have been a safe assumption, or maybe it was simply passable because there was so little competition in this area, and it's so revered now because there are so few cookbooks from that time. The bar has certainly been raised as it pertains to formatting a recipe, but has this contributed to the improvement of the home cook?

Let us know what you think in the comments.

Read last week's Alimentary Canal on Food Republic: What's In a Name?