We Support Soba: Everything You Need To Know About Japan's Most Underrated Noodle

Each day this week during Around The World In 5 Editors, one of the editors breaks in with a lineup of stories, recipes, interviews and personal essays dedicated to their respective country. Here is why today is dedicated to the food of Japan.

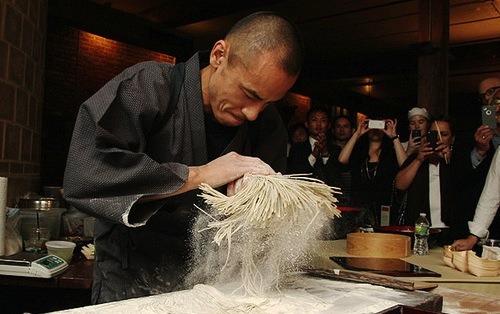

Mention "Japanese noodles" to the average person and chances are they'll assume you're talking about ramen. And we're not hating on that. Ramen is great – it's accessible, cheap and tasty. There are even maps that point you to the nearest ramen joint. But, as soba master Shuichi Kotani of NYC's Daruma-ya (and CEO of noodle consultants and educators Worldwide-Soba, Inc.) points out, "I don't know why ramen gets so much press... it's high in calories because of all the oil and it's high in salt." So, which worthy noodle does Kotani believe is taking a back seat? Soba! Buckwheat noodles are "healthy, light and refreshing," according to the expert. They're also available at a variety of dining establishments, from casual to extravagant.

About any major U.S. city doesn't just have Japanese restaurants serving soba, but shops that actually specialize in its production. With both hot and cold preparations, it's is a rare year-round comfort food. Since stumbling upon it a couple of years ago, I've visited neighborhood joint Soba-ya in NYC around 75+ times (during all four seasons, all hours of the day). By adding variety of toppings – from tempura to ikura to uni – the soft, wheaty noodles always take on new flavors. So, how to make it? Eat it? And just why hasn't it exploded onto the American culinary scene like its wormlike cousin? We caught up with Kotani and fellow NYC chef Toshio Tomita of slurp shop Cagen to talk all things buckwheat.

How is soba made?

SK: It's a tough process – one that I spent 10 years learning, as buckwheat can be difficult to work with. But, the basic rundown of the process is that I use a large portion of Japanese buckwheat flour and a smaller portion of American wheat flour. I blend the flours, sift them and add water. Then, I knead until the dough comes together. Eventually it forms a very smooth ball, which I roll into a circle. Once the circle is thin enough, I roll that around a pair of sticks so the dough is wrapped around it and cylindrical. Then I fold the dough and use a press and blade to cut the noodles. Finished noodles go into a special box so they aren't affected by any changes in temperature.

What is the proper way to eat it?

SK: It depends on the varieties of broth served with the noodles, as soba can come with thin soups or strong soups, sweet flavors or spicy flavors. The most common way of eating the noodles is zaru soba, or chilled soba, served with a dipping sauce and seaweed sprinkled on top. Take the noodles and dip them into the broth. Or, if you have warm broth, pour it over the noodles. And don't hesitate to slurp.

What are some mistakes that Americans often make when eating the dish?

SK: Being too hesitant to slurp!

TT: Timing. Don't let your soba linger! The dish is supposed to be eaten right away.

What are the most popular toppings? Any unusual ones that work?

SK: Popular toppings for soba in hot broth are mushrooms, duck and tempura, usually shrimp. For cold soba, sea urchin and bottarga are popular. More unusual ones that work are cold soba topped with sardines. We serve cold soba topped with grated yam.

What are the basic differences between soba and udon?

TT: The differences between soba and udon are in color and thickness – udon is thicker and whiter, because the noodles are made from wheat flour. In addition, udon is made with salt to add elasticity to the noodles, while soba does not contain any salt.

What about between soba and ramen?

TT: Unlike soba, ramen broth is never served cold. Ramen is an egg noodle and it has different flavored broths (miso, soy and salt), and meat stock (chicken, pork, etc.). Soba broth is made with fish stock, has a dipping sauce that is soy-based and is served cold in addition to being served hot.

Why does ramen get so much press in NYC while soba doesn't? What appeals so much about ramen to Americans?

TT: Ramen is part of the "college diet” and has been for many years because it is accessible and inexpensive. Its flavor is very similar to American comfort food, such as homemade chicken noodle soup. These factors both make it both appealing and familiar to New Yorkers and Americans alike. The press surrounding ramen has come from making this simple everyday meal into a sought-out specialty dish.

What are the nutritional benefits?

SK: Buckwheat noodles contain a variety of nutrients that are natural and healthy additions to one's diet. Not only are they excellent for mental and digestive health, they are also believed by many around the world to have properties that prevent diseases, as they are high in protein and contain various types of amino acids, such as lysine and arginine. These are essential building blocks for child development, growth and stamina.

Buckwheat contains more vitamin B1 – which is important for strength and to maintain a healthy appetite – than white rice. In addition, buckwheat contains more vitamin B2, which is good for the skin and helps prevent ailments like canker sores, as well as vitamin E, which is good for anti-aging. There's also choline, which prevents cancer and liver diseases, and polyphenols, which helps prevent the death of memory cells to reduce the risk of dementia or going senile. The list goes on.